A Legal Framework for DAOs (Part I)

This post originally appeared on a16crypto.com in August 2021 as part of Miles Jennings and David Kerr's series on domestic legal entity frameworks.1

If you'd prefer to read this article in PDF format, click here.

DISCLAIMER: This analysis should not be construed as legal advice for any particular facts or circumstances and is not meant to replace competent counsel. None of the opinions or positions provided hereby are intended to be treated as legal advice or to create an attorney-client relationship. This analysis might not reflect all current updates to applicable laws or interpretive guidance and the authors disclaim any obligation to update this paper. It is strongly advised for you to contact a reputable attorney in your jurisdiction for any questions or concerns. David Kerr is a recipient of a research grant from the DAO Research Collective.

Summary

The purpose of this paper is to identify a number of taxation, entity formation and operational issues pertaining to Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (“DAOs”) and to suggest a domestic entity structure capable of addressing such issues, including filing and paying U.S. taxes, opening an entity bank account, signing legal agreements and limiting liability for DAO members. A threshold question for determining the most appropriate domestic entity structure for a DAO is to determine whether it has a for-profit or not-for-profit purpose. Not for-profit purpose is not equivalent to tax-exempt and although very few DAOs will qualify as tax-exempt organizations, many may meet the requirements of not-for-profits for state law purposes. Accordingly, DAOs that meet the requirements should consider registration as unincorporated nonprofit associations (“UNA”) in states that recognize such an entity form.

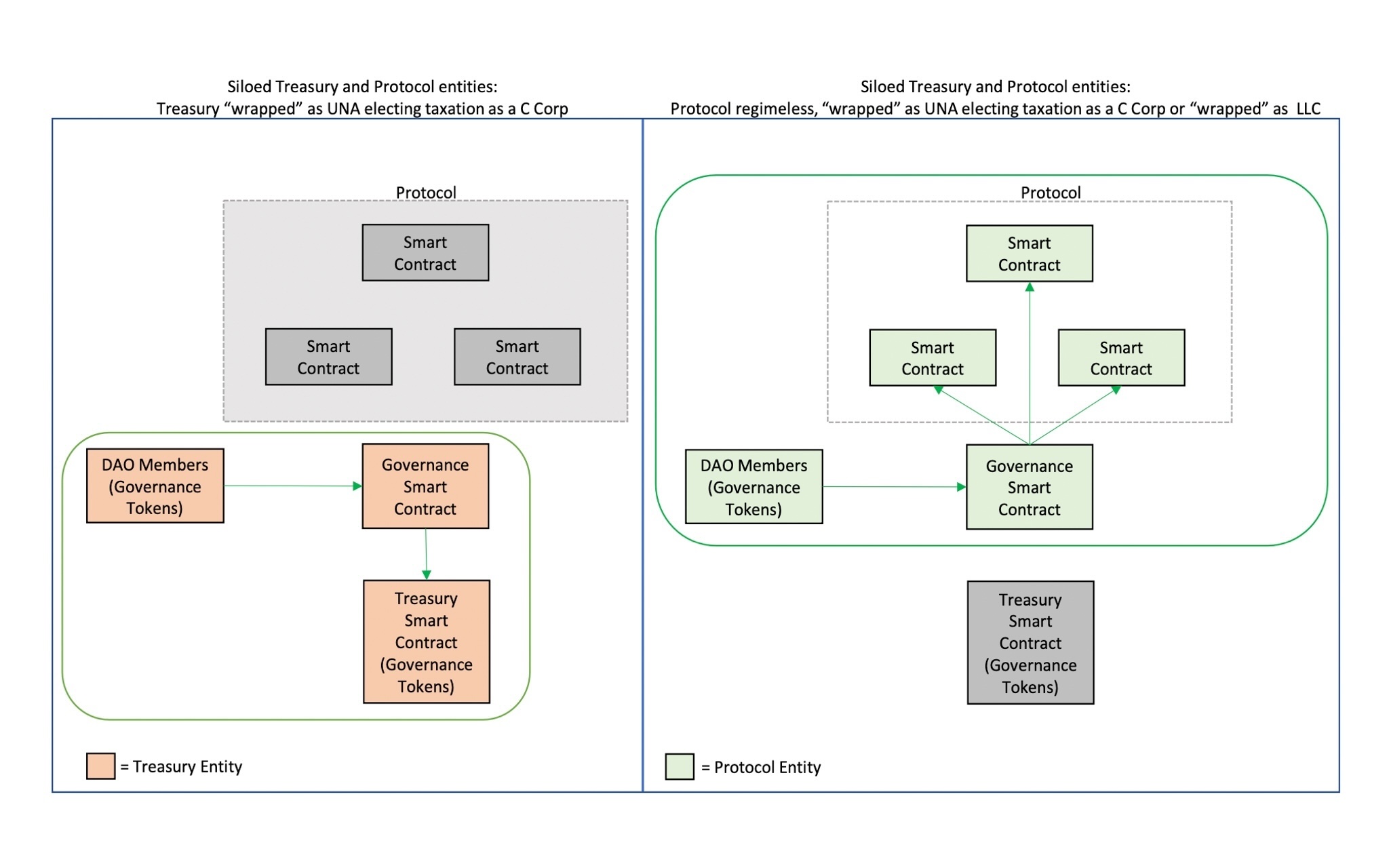

The following analysis raises the possibility of “wrapping” an entire DAO as a single UNA or “siloing” DAO activity between the treasury and the protocol, with the treasury being “wrapped” in an UNA and the protocol remaining regimeless or “wrapped” in a variety of possible entities, determined by the facts and circumstances of a particular DAO2. This would bring all activities related to the treasury (e.g., grant programs, DAO funded development work, staking/liquidity mining programs, treasury diversification, etc.) under the treasury UNA, whereas the separate activity relating to the protocol (e.g., protocol smart contract modifications, decisions relating to protocol fees, etc.) would fall under the separate and distinct protocol structure. In either case, the proposed structures prioritize trustless and on-chain transactions, while mitigating the risks of regimeless and offshored structures.

While the use of either UNA structure addresses many of the immediate concerns of DAOs, there remains a significant need for federal and state legislators to modify existing legal entity structures to make them sufficiently flexible for DAOs. DAOs share characteristics with partnerships, corporations, trusts and cooperatives, but the operational and organizational functionality derived from the technology itself presents issues in being classified within those existing entity structures. DAOs are analogous to partnerships, and yet not partnerships; analogous to corporations; and yet not corporations; analogous to mutual agencies; and yet not mutual agencies. As such, clarifying the options available to DAOs to attain existence as an entity in the United States would be a significant benefit to the development of decentralized ecosystems by eliminating ambiguity and making the technology more accessible to the public at large. In addition, it would foster further development of this emerging technology within the United States and facilitate the payment of U.S. taxes, for which DAOs may already be obligated.

Introduction

The United States regulatory environment surrounding digital assets presents an extraordinary challenge for blockchain and smart contract-based protocols. In the absence of comprehensive legislation addressing the complexities of this developing technology, individual regulatory agencies have been forced to provide their interpretations of how regulations should be applied to situations and technologies, well beyond what was considered when the current laws and regulations were enacted. Although it is universally agreed that comprehensive reform and new legislation is a necessity, the reality exists that the developers and users of blockchain technology have been left to navigate a patchwork regulatory environment insufficient to address relatively simple issues related to digital assets, let alone the additional complexity accompanying the decentralized alternatives to traditional financial service offerings available through smart contract-based protocols.

The vast majority of blockchain networks and smart contract-based protocols are organized as, or intend to implement, DAOs, which are member controlled organizational structures that operate absent a centralized authority3. While blockchain networks utilize a number of different consensus mechanisms, DAOs of smart contract-based protocols are typically facilitated by a set of governance-related smart contracts that have specified control rights with respect to the smart contracts making up the underlying protocol, all of which are built on distributed ledger technology, most commonly the Ethereum blockchain. These governance smart contracts disintermediate transactions between counterparties by automating the decision-making and administrative processes typically performed by traditional management structures. Decentralization of a given protocol occurs when control (e.g., governance) of the non-immutable aspects of a protocol’s smart contracts is passed from the developers to the members of a DAO via the activation of governance smart contracts.

Decentralized Finance (“DeFi”) protocols are one example of smart contract-based protocols. DeFi protocols provide alternative mechanisms to perform many traditional financial services that are, often times, highly regulated themselves (i.e., payments, swaps and derivative transactions, insurance, asset trading, lending and investing). As the functionality of many DeFi protocols deviates significantly from traditional financial services, significant interpretive obstacles exist in determining the manner and extent that existing statutory authority is applicable. Although the SEC, CFTC, FinCEN, OFAC, IRS, Department of Treasury and state regulators have issued guidance and interpretations concerning digital assets, the issues highlighted in that guidance and the concentration of accompanying enforcement actions has resulted in a prioritization of the following: (i) identifying the applicability of SEC and CFTC registration requirements, (ii) taxation of virtual currency as property and the need for taxpayers to include virtual currency activities on their tax returns and (iii) the implementation of BSA compliant Anti-Money Laundering (“AML”) and Know Your Customer (“KYC”) programs.

However, as a result of increased public scrutiny concerning shortfalls in income tax collection and significant projected budget scoring benefits, Congress has recently considered multiple legislative proposals intended to increase third-party reporting requirements for virtual currencies4. As with any legislative development in a rapidly evolving field, any previous conclusions pertaining to tax planning must be reassessed and updated to ensure that appropriate tax compliance requirements are being met. The purpose of this analysis is to identify a number of emerging issues pertaining to DAOs and, ultimately, to suggest a domestic entity structure capable of filing and paying U.S. taxes, opening an entity bank account, signing legal agreements and limiting liability for DAO members.

Taxation of DAOs and Regulatory Reporting Requirements

The Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) serves a dual role as an administrative organization responsible for assisting taxpayers in meeting their tax obligations and as an enforcement organization responsible for ensuring the full payment of tax in accordance with the law5. Although the IRS has issued limited guidance on digital assets beyond announcing its opinion that virtual currency should be treated as property for purposes of income taxation6, the IRS has been very active in communicating the need to report virtual currency income on tax returns and utilizing its enforcement authority to gather information about taxpayers with significant virtual currency activity7. Although the asymmetric nature of heavily enforcing compliance, while simultaneously releasing minimal guidance around digital assets might appear contradictory, it is consistent with the IRS’s role and authority to administer and enforce internal revenue laws.

The U.S. Treasury Department and the IRS are part of the executive branch and although Congress often delegates some of its rulemaking authority to the U.S. Treasury, it is Congress that is vested with the power to legislate tax laws under the U.S. Constitution. Accordingly, the U.S. Treasury can issue regulations that have the force of law, but only when the U.S. Treasury is acting pursuant to congressional delegation. However, when the IRS or the U.S. Treasury is acting pursuant to the general executive branch power to enforce the law, they are prohibited from unilaterally making binding tax law and have a long history of being curtailed by the judicial system for expanding their authority beyond reasonable interpretations of existing statute8.

The limitations on the IRS being able to provide guidance on digital assets without further authority from Congress and the functionality provided by DeFi protocols not considered under existing tax laws have created many areas of ambiguity regarding taxation, which can generally be divided into tax reporting requirements and potential income tax liability for purposes of discussion.

Tax Reporting Requirements

In spite of a taxpayer’s obligation to pay income taxes on income from all sources, the overwhelming majority of reported and taxed income results from information or withholding that is provided by third-party intermediaries via “information returns” obligated under the IRC and various regulations9. It is estimated that only 45% of income is reported in areas where the IRS does not have informational reporting mechanisms to evaluate taxpayer returns for compliance, resulting in an estimated $600 billion tax gap through 2019 and a projected $7 trillion dollar tax cap estimated through 203110.

In response to the potential for virtual currency to disrupt third-party reporting requirements and the scoring benefits that projected tax revenue would have in offsetting the costs of legislation, the U.S. Treasury Department recently proposed an expansion of the scope for reporting obligations regarding cryptocurrencies, crypto asset exchanges and crypto payment services. Specifically, the U.S. Treasury proposed that cryptocurrency exchanges and custodians report gross inflows and outflows of cryptocurrency on the existing form 1099-INT and businesses report cryptocurrency transactions above $10,000 on Form 830011. Although the Treasury proposal has been removed from the American Families Plan, an amendment of even broader scope has been made to an infrastructure bill that would require the reporting of transactions above $10,000 and include a wide definition of digital asset transactions as broker activity for the purpose of 1099 reporting requirements12.

Even though the manner in which this type of proposed legislation has been raised is transparently motivated by the optimistic projections of its legislative scoring benefits13, if the proposed amendment were to become law, it would nevertheless increase the tax reporting obligations on a wide array of activities pertaining to digital assets. However, given the complexity of the Internal Revenue Code, Treasury Regulations, tax related case law and general ambiguity related to the taxation of digital assets, this type of piecemeal legislation is likely to result in a number of unintended consequences for taxpayers, further underscoring the need for comprehensive and considered legislation regarding the regulation and taxation of digital assets14.

Although no legislation updating the existing tax reporting requirements of digital assets has been passed into law, changes to the existing tax reporting requirements are likely imminent and DAOs must examine their activities to determine the applicability and impact of proposed changes in law.

Potential Income Tax Liability

In 2014, the IRS issued Notice 2014-21, establishing its position that virtual currency should be treated as property for U.S. federal income tax purposes and providing examples of how existing tax principles applied to virtual currency15. The notice relied on the definition provided in the 2013 FinCEN guidance stating that “[v]irtual currency that has equivalent value in real currency, or that acts as a substitute for real currency is referred to as ‘convertible’ virtual currency.”16 As such, the IRS definition of virtual currency can reasonably be interpreted to include crypto tokens for the purposes of this analysis.

The classification of virtual currency as property results in a capital gain or loss from the sale or exchange of virtual currency held as a capital asset, while the receipt of virtual currency as payment for goods or services results in ordinary income (determined by converting the virtual currency into U.S. dollars at the exchange rate at the relevant time and in a reasonable manner that is consistently applied).

The foregoing is relevant for DAOs to consider in the context of several scenarios, including the following:

- Taxation of Governance Tokens

- Taxation of DAO Treasury Activities

- Responsibility to File Returns and Pay Tax

Taxation of Governance Tokens17

In order to analyze the tax obligations associated with governance tokens (particularly those retained within a DAO’s treasury), it is necessary to understand the general way in which DAOs are formed. At a high level, a developer (often a U.S. incorporated entity) creates the code that underlies the smart contracts of the protocol18. The code is released on the internet as open source and the smart contracts become operational when deployed by a user to a blockchain, such as Ethereum. Practices vary with respect to the retention of copyright interests and licensing of the open-source code for future commercial uses.

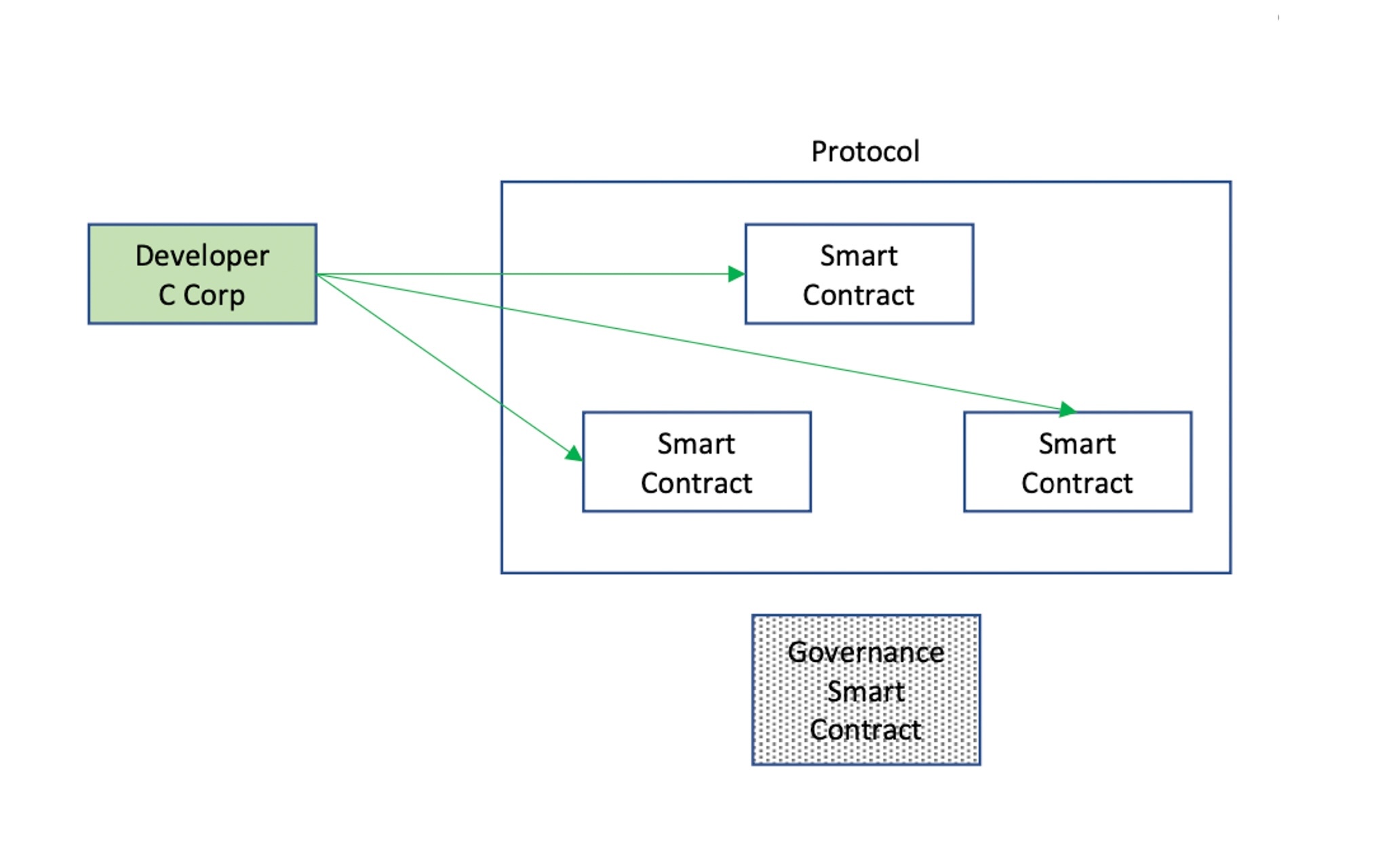

When first deployed, the developer corporations typically retain control over certain aspects of the smart contracts themselves to oversee the operations of the protocol while it gains an initial user base and enable the addition of new features over time (see Chart 1).

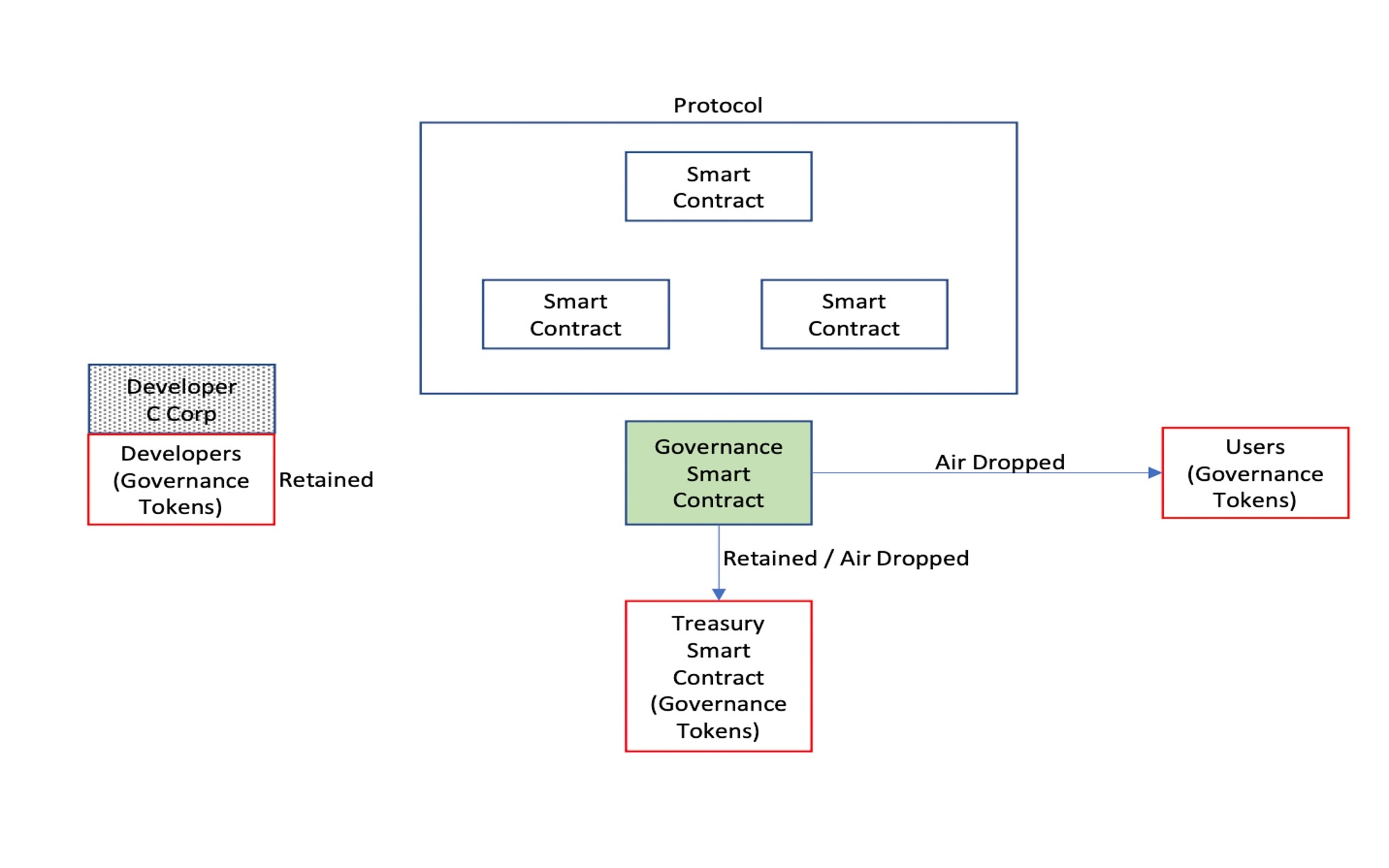

When the governance smart contracts are activated, control of the protocol smart contracts is passed from the developers to the holders of the governance tokens, which are typically distributed to protocol users through an airdrop and to employees, shareholders and advisors of the developer corporation pursuant to existing agreements, retained in the treasury and retained by the developer corporation for future use, thereby creating the DAO (see Chart 2).19

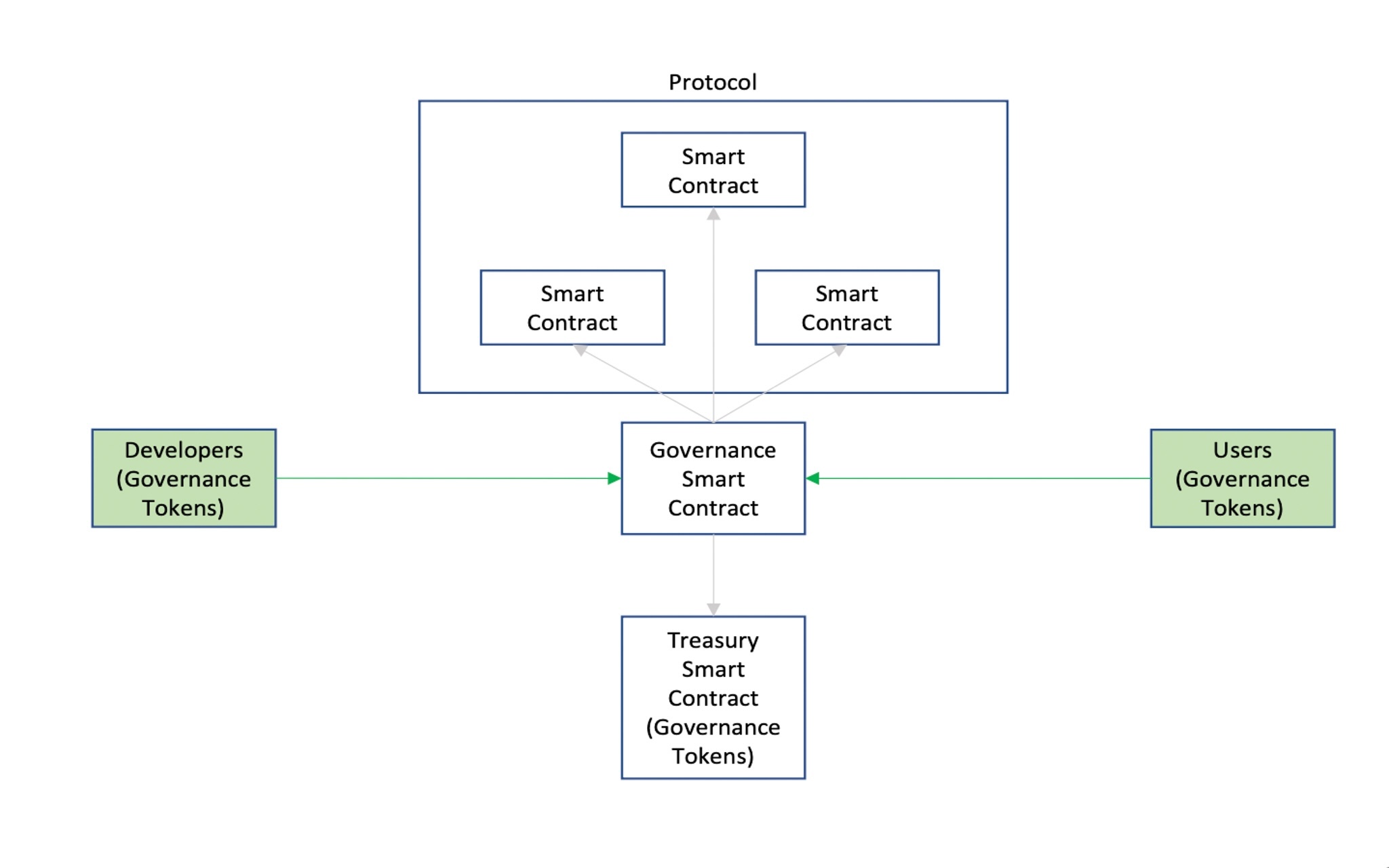

The governance tokens provide decentralized decision-making mechanism for DAO members to interact with the governance protocols and control the smart contracts underlying the protocol (see Chart 3). Although the functionality of governance tokens and governance smart contracts vary for each DAO, governance tokens generally provide a means in which proposals can be raised and voted on regarding DAO operational decisions and governance smart contracts generally provide a means to alter variants in the smart contracts of the underlying protocol and to manage the DAO treasury.

As most governance tokens have a fair market value and are transferable, they are subject to income taxation. Although application of IRS Rev. Rul. 2019-24 results in a fairly straightforward analysis for holders of the tokens (ordinary income is realized when they have dominion and control over governance tokens and capital gains or loss is realized upon the sale of a governance tokens), there are some complications in identifying the tax treatment of governance tokens retained in the treasury smart contracts20.

There is no standard method utilized by DAOs to transfer tokens to a treasury, as treasury’s tokens can be created within the smart contracts when the governance protocols are activated or be air dropped directly into a treasury’s smart contracts. Regardless of how a treasury is funded, under an application of Section 61 of the IRC and the Supreme Court’s holding in Glenshaw Glass consistent with the IRS’s guidance to date, the tokens within the treasury would result in a taxable event for any U.S. taxpayer that is deemed to have dominion and control over such tokens21.

Taxation of DAO Treasury Activities

As originally contemplated, DAO treasuries were intended to benefit the underlying blockchain protocol by incentivizing user activity (most often through staking/liquidity mining) and by funding further developments in decentralized technology. However, given significant increases in the locked-in value of many treasuries and the expansion of functionality of many governance tokens, many DAOs are now capable of generating significant income from their treasuries and are pursuing a much wider range of activities, including lobbying and the funding of grants. This has introduced complexities to the analysis of the potential tax treatment of DAOs and has increased the need for strategic tax planning, particularly for those DAO treasuries that were established by U.S. Developer Corporations. In particular:

- Staking/Liquidity Mining Programs22

- Disposition of a treasury’s governance tokens, including as part of a staking or liquidity mining program, result in the recognition of capital gains or losses, as applicable. Any such program would need to be carefully evaluated based on the facts and circumstances of the DAO operations to determine what, if any, tax reporting or withholding requirements should be made in relation to the income received by participants in such programs and who within the operation of the DAO should be responsible for the execution of those activities.

- Grant/Lobbying Programs – As with the staking and liquidity mining programs, a disposition of a treasury’s governance tokens as part of a DAO grant or lobbying program would be taxable. Although such programs could be constructed as non-profits exempted from the payment of federal taxation, unless the treasury itself has elected federal tax treatment as a Section 501 exempt entity23 – any tax incurred at the Treasury level must paid prior to being distributed to a grant or lobbying program to avoid an improper assignment of income.

- Portfolio Diversification – If the exchange of DAO treasury assets for other assets to be retained under the control of the DAO are not properly recognized as tax events, a significant shortfall in tax revenue could exist. Accordingly, any diversification of DAO treasury assets must be evaluated on the facts and circumstances of a particular DAO.

Responsibility to File Returns and Pay Tax

Enacting a decentralized system of control is a difficult task to undertake without complications. Turning over control of a DeFi protocol to a DAO must be balanced by a period where governance token holders are educated and grow into their responsibilities to promote responsible and educated governance. Absent a soft transition period, a DAO faces many threats if it too freely releases governance of its protocols. That balance can be found in many DAO’s decisions to place limitations on how governance proposals can be made, staggering the release of governance tokens so that the voting rights of users become stronger over a period of years, maintaining governance of the smart contracts until releasing governance tokens, retaining the access necessary to address cyberattacks and placing reasonable restrictions on the type of activity the treasury is authorized to execute to prevent self-interested or malevolent parties from improperly gaining control of the DAO.

From a U.S. tax perspective, these justifiable limitations on decentralized governance present certain complications. For the purposes of entity existence and tax responsibility, they could be construed as a period where a U.S. incorporated entity exercises control over activities that contributed to the valuation of the governance tokens. During this period of U.S. incorporated control (pre-distribution of governance tokens) or quasi-U.S. incorporated control (post-distribution of governance tokens with limitations), the value or potential value of the assets might have already appreciated significantly or established direct ties to U.S. citizens or U.S. corporations. The activity during this period must be carefully evaluated on the facts and circumstances of each DAO to make sure that the developer corporation did not have any reporting, withholding or income recognition for the operations of the DeFi protocol when under its direct control and that it did not retain any reporting, withholding or income recognition obligations post the activation of the governance protocol.

Even after passing full control through the governance protocol, the determination of dominion and control is not obvious when it comes to a DAO treasury’s tokens. The treasury’s tokens are only accessible through executing a smart contract that contains specific requirements as to what transactions are permissible (e.g., governance protocols sometimes exclude a wide variety of transactions that would be harmful to the intended purpose of the DAO) and holders of the governance tokens are unable to exert individual dominion over the tokens (e.g., an individual user would typically be unable to unilaterally propose and approve any disposition of treasury assets).

Existing case law establishes that restrictions on an asset holder’s ability to exercise of dominion is, in and of itself, an exercise of dominion and control sufficient to create an income event, which would be evident had the holders of the governance tokens elected to fund the treasury themselves24. However, the holders of the governance tokens typically receive their tokens at a time when the DAO treasury is subject to the restrictions of the governance protocols and do not themselves elect to restrict their own control of the treasury. Accordingly, there is no justification that the tax liability should be attributed to the token holders themselves, unless they are imputed ownership of the treasury through a pass-through entity structure.

At formation, many DAOs have elected to avoid entity structures in anticipation of legislation more applicable to DAO entity structures than what the law currently provides. However, the unanticipated rate at which the treasuries have grown in value and the increasing need for DAOs to engage in activities to support their ecosystems has created significant pressure on regimeless DAOs to address their inability to file and pay taxes associated with income tax events within the treasuries. Accordingly, creating a taxable entity capable of filing and paying taxes would significantly decrease the risk associated with the regimeless structure because the inability to pay income tax would be remediated.

Existing DAO Entity Structures Discussion & Analysis

Entityless & Regimeless Structures

DAOs face a variety of issues in trying to form within the existing options for U.S. entity structures because the available entity structures are designed for centralized operations, which is inherently incompatible with a decentralized operational structure25.

For instance, a legal entity controlled by individual human beings could undercut the decentralization of the protocol by making such individuals active participants, which the Staff at the SEC has stressed the importance of avoiding for purposes of the Howey test. Additionally, declaring a fictional business purpose is incongruent to the purpose of a DAO and the formality required to operate an incorporated business entity could negatively affect the development of the underlying technology. Although the smart contracts of a governance protocol interact with the blockchain to provide functionality, that process is reflective of the intentions of those governing the smart contracts, the application of which is akin to a tool designed to enact the decisions made by membership voting. Operations occurring off-chain are not inconsistent with decentralization by their existence, but if an off-chain operation creates an obstacle for how the DAO community can accomplish its objectives (i.e., natural persons serving as Directors with legal standing over the wishes of the DAO community), then the decentralized governance of the operation has been co-opted by a centralized mechanism.

In addition, the existing structures under United States law do not provide an obvious path for selecting an entity structure and many aspects of the tax treatment of DAOs formed by U.S. persons or entities is uncertain. Regulatory restrictions limiting the number and accreditation of investors, size restrictions, the observance of corporate formalities and a lack of intent from governance token holders to form an incorporated entity all contribute to the ambiguity of what entity structure is appropriate for a DAO26. Although the passing of legislation recognizing DAOs as legal entities (e.g., “Wyoming’s DAO Law”) is indicative of progress in the need for DAOs to be recognized as an entity structure, absent recognition at the federal level and significant clarity around the various forms of DAOs, the utility of such entity structures is not beneficial to many DAOs.

Unfortunately, a DAO’s decision to not create a legal entity does not offer protection from responsibilities that may arise in the operation of a DAO. From a legal perspective, when two or more individuals are engaged in even a tenuous business relationship, the imputed structure is that of a general partnership27. Significant legal precedent exists for U.S. courts utilizing a functional approach to determining whether a partnership was formed irrespective of disclaimers and specific intent to not form a partnership28. General partnerships have no corporate form and do not provide partners with the liability limitations contained in other common entity structures (e.g., LLCs, C-Corps, etc.).

In a practical sense, the operational structure of a DAO provides certain advantages against liability as the smart contracts prevent much of the legal risk of a typical organization by providing an unambiguous and efficient method for transactions to be processed. Consequently, exposure to creditors or nonchain entities may be limited. However, if a judgement were to be entered, accessing DAO resources would require a vote of the widely dispersed and pseudonymous members, who could be unwilling to utilize treasury assets to satisfy any judgement, increasing the risk that such liability falls on individual DAO members. To date, DAOs have generally been very active and supportive of efforts to reimburse users for losses associated with smart contract failures or exploits29. As such, the likelihood of significant harm may actually be quite low, providing that a DAO has access to sufficient funds to cover the cost of any judgements and that DAO members are inclined to release the funds through a validly executed governance proposal30.

From a tax perspective, the risks are much more acute. For taxation purposes, the default filing status imputed onto groups is also a general partnership and there is a robust library of case law where this has occurred31. Although the facts and circumstances of most DAOs present a situation where the lack of a business purpose would likely prevent a partnership from being imputed, given the mechanics of how a DAO with strong ties to the U.S. is formed, it is also likely that the tax liability associated with the treasury would still be attributed to the developers, the DAO itself or directly to its members.

Despite public perception that corporate tax inversions and internet-only operations provide a haven for tax evasion, the reality is that base erosion has long been a concern of the United States and worldwide governments, and activities in this space require significant tax planning to be effectuated in a legally compliant manner32. Asserting that a DAO exists in a foreign jurisdiction or is solely contained in digital cyberspace while having significant development performed in the United States, U.S. sourced income tied to the value of the governance tokens and control exerted for a period of time by a U.S. entity could weaken the position that such a DAO is entirely separate from the United States for the purposes of U.S. income tax purposes.

Offshore Entity Structures

An increasingly utilized mechanism for resolving DAO entity structure issues has been the practice of offshoring governance tokens to foreign jurisdictions with favorable tax regimes (e.g., the Cayman Islands, BVI, Panama, Singapore, Ireland and Switzerland) and wrapping the DAO in a foundation entity formed in such jurisdiction (“Foreign Foundation”). The potential benefits to this type of structure are obvious in that not only does the Foreign Foundation provide an extremely flexible framework that would support off-chain functions bound to executing validly executed proposals passed through a DAO’s governance protocols, but the favorable tax regimes offer DAOs potential tax savings regarding their treasuries.

Although the high costs associated with establishing such Foreign Foundations are often cited as a barrier to entry for most DAOs, there are also risks associated with an offshoring strategy.

In general, a foreign operation found to have a U.S. trade or business has effectively connected income which will subject it to U.S. income tax on the portion of the income that is effectively connected to that U.S. trade or business33. If a foreign operation’s intellectual property was developed in the United States, or key employees or directors were present in the United States for significant periods of time, the IRS can attribute the portion of business being conducted in the United States as taxable and require the necessary tax filings, tax reporting and payments to resolve34.

Accordingly, U.S. developers and any DAO with a protocol developed in the United States must carefully consider whether related activities undertaken in the United States create a taxable presence in the United States both for federal and state income tax purposes regardless of any foreign structuring. The implementation of any offshore structure should not be attempted without the advice of counsel and international tax experts.

Tax Planning Issues

The increase of DAOs creates an environment where there is tremendous diversity in operations. While an entirely on-chain operation may be analyzed differently in relation to its tax liabilities, the DAO exists in a physical medium comprised of its members and treatment of one does not necessarily apply to another. Many DAOs are not developed by U.S. developers and present an entirely different analysis than those developed by U.S. persons or entities.

U.S. developers and associated DAOs should adopt an approach to ensure any potentially significant U.S. income tax liabilities surrounding the treasuries are being paid and tax returns are being filed by an appropriate entity35. Although there may not be a perfect mechanism to minimize all the risks surrounding taxation and reporting requirements, taxpayers who have historically made legitimate good faith efforts to comply with unclear income tax compliance responsibilities are afforded significantly more grace than those who capitalize on any complexity as a justification to evade any tax responsibility whatsoever.

Potential Entity Structures

In the United States, several incorporated and unincorporated structures exist that provide liability protection. Incorporated structures create a separate legal entity for the purposes of pursuing an agreed upon business venture, whereas unincorporated structures are created by contract and controlled by state law in the pursuit of a shared objective. The form of that determination results in an entity responsible for filing tax returns, paying tax, reporting the tax obligations of its members or submitting the necessary documentation to maintain tax exempt status, as applicable.

The incongruity of many DAOs intended purpose with an incorporated business structure is evident. While there are certainly situations where the purpose of a DAO is for the members to join in the pursuit of a shared business purpose (a particularly infamous example of this arrangement would be the 2016 organization known as “The DAO”)36 – most DAOs do not have a shared business or for-profit purpose, nor any intent to develop one.

For-Profit or Not-For-Profit Intent

Although the mechanization of governance varies by protocol, in general, the primary functionality of a governance protocol is not to make profit, but to create and vote on governance proposals that control the smart contracts of an underlying protocol and direct the actions of the DAO treasury to foster the development and growth of a decentralized ecosystem. Governance tokens are digital assets that represent voting power within a DAO and are integral to decentralization because they distribute powers and rights to users.

The fact that governance tokens have a market value that, in many cases, significantly exceeds the functionality and current value of the underlying smart contracts (while still being tied to the underlying functionality of the services provided by the smart contract) complicates that conclusion. However, the increased value of the governance tokens is not the primary intent of the DAO, it is simply reflective of the current market for the functionality DAOs provide and the highly volatile market in which they exist. Accordingly, if a DAO’s primary purpose is to develop and share an innovative technology that creates a more efficient and transparent financial system, any increase in value to the governance tokens is incidental and, given the highly volatile digital asset market, not necessarily directly tied to their efforts.

A real-world example that helps illustrate this point can be found in the primary purpose of a Homeowner’s Association, which is to protect neighborhood standards by enforcing the codes and covenants of the community in which the members all are personally invested in the value of their home and may even include beautifying public areas, building amenities or assessing members to pay for necessary repairs. Any increase in value of the members’ homes is incidental to their primary purpose and often, indicative of a larger trend in the housing market itself. However, an HOA’s involvement in enforcing the codes and covenants does not rise to the level of for-profit activity, even if the reason behind their activities is to protect home values and the homes values rise significantly.

Several other factors that may impact the analysis of whether a DAO is for profit. For example:

- Initial Token Distribution – Governance tokens are typically not sold when distributed by DAOs, but freely given to users of the technology37.

- Limitations on DAO Token Distributions – Although many DAOs limit the use of governance tokens contained in their treasuries for a period of time, ultimately DAOs typically are not restricted in how they elect to use treasury assets. However, there are many practical limitations regarding a DAOs ability to distribute treasury assets to its members that would provide clear disincentives for this type of activity. For instance, such action would likely result in the immediate cessation of decentralized project development, dilution of all token holders such that the price decrease would likely offset the value in any new tokens received and the significant possibility of a fork of the protocol.

- Revenue and Revenue Distributions – Many DAOs produce taxable revenue and some even distribute that revenue to members38.

Ultimately, every DAO must be analyzed on its individual facts and circumstances when evaluating possible entity structures. However, as discussed in the next section, the existence of taxable revenue or member profit is not necessarily dispositive of a for-profit intent.

Uniform Unincorporated Nonprofit Association Act (“UUNAA”)

Nonprofit entities are organized under state law and each state defines nonprofit differently, with the organizational requirements, legal privileges and liability protections varying widely between jurisdictions39. Historically, nonprofit associations were default organizations found in the absence of charitable trusts, nonprofit corporations or any associations “organized under statutory law that is authorized to engage in nonprofit activities.”40

Under common law, nonprofit associations were considered extensions of its individual members and not legal entities. Accordingly, “nonprofit associations could not hold or convey property in its own name or sue or be sued in its own name.”41 However, many jurisdictions enacted statutes to govern the legal aspects of nonprofit associations and provide nonprofit associations legal existence as an entity, resulting in significant deviations in treatment in jurisdictions across the United States. Stated plainly by a Texas Court in 1992, “[u]nincorporated associations long have been a problem for the law. They are analogous to partnerships, and yet not partnerships; analogous to corporations; and yet not corporations; analogous to joint tenancies, and yet not joint tenancies; analogous to mutual agencies; and yet not mutual agencies.”42

In furtherance of its effort to bring “clarity and stability to critical areas of state law,” the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (“NCCUSL”) endorsed the original UUNAA in 1996 and updated a more comprehensive version in 2008, that was last amended in 201143. When adopted by a state, the UUNAA governs all nonprofit associations formed or operating in regard to the following:

(1) definition of the types of organizations covered; (2) the relation of the act to other existing laws; (3) the recognition that a nonprofit association is a legal entity and the legal implications flowing from this status, including the ability of a nonprofit association to own and dispose of property and to sue and be sued in its own name; (4) the contract and tort liability of a nonprofit association and its members and managers; (5) internal governance, fiduciary duties, and agency authority; and (6) dissolution and merger44.

Although there is minimal case law where courts have construed the UUNAA as adopted by a state, the methodology utilized by courts that have interpreted their state’s UUNAA statutes included consideration of the comments associated with the UUNAA as persuasive authority because “the legislature presumably considered those comments when adopted.”45 Accordingly, any DAO wishing to form a UNA must consider the UUNAA comments in addition to the laws of the state in which it intends to register.

Applicability of UUNAA to DAOs

While many states enumerate a charitable purpose or goal within the definition of nonprofit, those that have adopted the UUNAA unabridged define a UNA as “consisting of [two] or more members joined under an agreement that is oral, in a record, or implied from conduct, for one or more common, nonprofit purposes.”46 However, the UUNAA does not define the term “nonprofit,” stating that “[a]n enacting jurisdiction can choose to expand or reduce the number of types of exclusions consistent with the concept that a nonprofit association is a default form of organization for unincorporated nonprofit entities.”

If a state has not chosen to limit nonprofit associations to those with charitable purpose, then the UUNAA and its comments must be analyzed to determine how a DAO’s activities would qualify as nonprofit47. The comments from the UUNAA are instructive in this areas and state that:

Many existing unincorporated nonprofit organizations engage in activities that are intended to produce a profit, e.g., a bingo parlor operated by a church where the profits are used to buy food for a homeless shelter. This type of profit-making endeavor should not disqualify the organization from being a nonprofit association if it otherwise qualifies. A for-profit activity might endanger the tax-exempt status of the organization or may generate taxable income, but these are separate issues and should not affect the organizational status of a nonprofit association or the rights and liabilities of its members and managers. The fact that some or all of the members receive some direct or indirect benefit from a nonprofit association’s profit-making activities will not disqualify an unincorporated nonprofit organization from being a nonprofit association under this act so long as the benefit is in furtherance of the nonprofit association’s nonprofit purposes. The distribution of any profits to the members for the members’ own use, e.g., a dividend distribution to members, would, however, disqualify the organization from being a nonprofit association because the distribution is not made in furtherance of the nonprofit association’s nonprofit purposes. The organization would be a general partnership, the default organizational form for a for-profit organization. An unincorporated investment club that distributes its profits to its members, for example, would be a general partnership and not a nonprofit association even though its stated purpose is to educate its members about investments.

This above comment from the UUNAA establishes a framework for DAOs to analyze their activities, particularly the distributions of profits to its members48. Many DAO protocols utilize staking and liquidity mining that generate profits, which are reinvested within the protocols or paid out as expenses necessary for the protocol to function. Although these activities must be addressed for the purposes of income tax payment and tax reporting, their existence appears to be within the activity described in the UUNAA comment section. Similarly, taxable events within the treasuries would reasonably be included within the furtherance of its nonprofit objectives as the existence and activities of the treasuries is demonstrative of the DAOs not for-profit intent.

Where the UUNAA is restrictive on DAO activities involves distributions of profits for the members’ own use, which would be disqualifying of the organization being a UNA. If a DAO were to make distributions of profits to its members in a manner inconsistent with its nonprofit purpose, it would not maintain the liability limitations of a registered UNA.

Although a DAO could rid itself of all risk from engaging in for-profit activities by limiting the available functionality of the smart contracts in a manner immutable to even its governance proposals. However, this would severely hinder the ability for DAOs to function as an effective decision-making body and deprive it of the agency necessary to adapt to future changes. A potential solution DAOs could adopt to limit the risk regarding distributions would be to tailor the smart contracts to prevent distributions for a period of time, thus preventing the execution of any governance proposals inconsistent with its nonprofit purpose. Although this restriction is not strictly necessary to demonstrate a nonprofit intent, it would be consistent with other forms of governance restrictions utilized by developers to steward the adoption of a nascent technology.

Ultimately, it is possible that the membership of a DAO could decide that they wished to profit from some aspect of the protocol. Although the mechanics of such a transition in change of entity structure or change in operation would need to comply with state law and be tailored to a specific DAO’s facts and circumstances, the mere potential for a DAO membership to one day profit from an operational change is not evidence of a for-profit intent. Although the case law on this issue is mostly defined by for-profit activities that is consistent with a nonprofit purpose and examples exist of disqualifying distributions - even the limited number of cases reference situations where associations have been able to make distributions that directly benefit their members.

In analyzing this issue, one court wrote:

"Nonprofit" is not defined. A common definition — it is an association whose net gains do not inure to the benefit of its members and which makes no distribution to its members, except on dissolution — does not work for all nonprofit associations. Consumer cooperatives, for example, make distributions to their members; but they are not for-profit organizations. Those consumer cooperatives not organized under specific state or federal laws need the benefits of this Act.49

Although a Texas State Circuit Court of Appeals decision is not controlling law, it is confirmation that members of registered UNA have been allowed to distribute revenue to its members without automatically being considered for-profit and may leave room for carefully constructed positions to allow DAOs to operate in a similar fashion, while still maintaining the liability protections of a registered UNA.50

Liability Protections of UUNAA for DAOs

Adoption of the UUNAA makes an UNA a legal entity separate from its members in determining and enforcing rights, duties and liabilities in contract and tort, which provides significant benefit to members of UNAs. When assessing the liability protections afforded through adoption of the UUNAA, a Colorado court stated:

There is no case law construing or applying this provision of the Association Act. The Association Act makes a nonprofit unincorporated association a legal entity separate and apart from its members. Therefore, logically, nonprofit unincorporated associations are more in the nature of corporations, limited partnerships, or limited liability companies. This basic and fundamental change has a considerable impact on the liability of members and others for the liabilities of nonprofit unincorporated associations. The official comments make these changes, and their implications, clear.51

Although it is essential that a DAO wishing to register as a UNA ensure that its operations are consistent with the requirements, the limited liability protections afforded the members of a DAO through registering as a UNA are potentially expansive. 52

Agreement to Join Unincorporated Nonprofit Association for DAO Members

One of the difficulties faced by DAOs, especially those already operating with active governance protocols, is meeting the formalities necessary to join an entity structure. In most cases, decentralized governance provides an inherent obstacle to decisions on entity structuring. In general, any decision to incorporate an entire DAO with a state authority requires an affirmative act made by each of the holders of the token. Even a majority vote that cleared the applicable governance protocol approval thresholds would not meet the requirements necessary to form an entity because any dissenting member would not be bound by the decision to form an entity. This presents a significant limitation on the options presented to DAOs that have already released their governance tokens.

However, the requirements for member participation in a registered UNA are significantly less cumbersome and present a viable path for an already operating DAO to utilize its governance protocols to form an agreement sufficient to establish the holders of the governance token as members of the entity through their continued membership in the DAO.

The UUNAA describes its legal requirements for membership as follows:

“Agreement” rather than “contract” is the appropriate term because the legal requirements for an agreement are less stringent and less formal than for a contract. For example, mutual consent must be present in both but the contractual concept of consideration is not necessary for an agreement. The agreement to form a nonprofit association can be in a “record” (see subsection (7)), or oral, or implied from conduct (e.g., course of performance or course of dealing). The agreement to form a nonprofit association becomes part of the nonprofit association’s overall “governing principles.” “Implied from conduct” rather than “implied from its established practices” (see subsection (2)) is used as the standard because the agreement to form a nonprofit association precedes or is contemporaneous with its existence, and established practices can only exist after the nonprofit association is in existence.

Accordingly, a validly executed governance proposal forming a UNA and the continued participation of its members through their governance tokens would be indicative of the type of conduct indicative of sufficient member agreement.

Transferability of Membership Interests amongst DAO members

Although the default language of the UUNAA indicates that membership interests are not transferable, it does allow for nonprofit associations governing principles to dictate when transfers would be allowable. 53 As governance tokens are designed to be freely transferable, they provide an obvious intent for membership in the DAO to be freely transferable.

“Siloed” DAO Entity Structures

An inherent difficulty that has arisen from the rapid developments in functionality of digital assets has been determining how existing regulatory, taxation and accounting principles should be applied. Cryptocurrencies and tokens alone have spawned a variety of categorizations beyond just a medium of exchange or a store of value through the benefit to which end-users are entitled. A single token can give access to a variety of services and functionality can even change over time. 54 Much consideration has been given to the how this “hybrid” functionality of tokens presents an obstacle in assessing how a token should be treated, but the absence of traditional functionality is equally important in appropriately classifying how a token should be treated under the law, which is particularly relevant to governance tokens as related to DAOs.

When viewed from the functionality conveyed to its users, it is apparent that the governance tokens of most DAOs provide two distinct operational purposes that are directly tied to how decentralization is achieved, delineated by:

- user interaction with the treasury; and/or

- user interaction with the protocol.

Most governance protocols provide a significant amount of discretion to members regarding how the treasury is deployed and proposals can take many different forms, including distribution of grants, DAO funded development work, staking/liquidity programs and treasury diversifications. In order to be executable, the governance proposals often require additive smart contracts that provide the code necessary to actually enact the proposals. Additionally, many of the intended purposes of treasury proposals involve authorizing real-world individuals and entities to execute the stated purpose of the proposals (e.g., members of grant committees, board of directors for 501(c)(4) entities funded through the treasury or identifying individuals capable of performing work that benefits the DAO’s objectives). This form of democratic and decentralized governance is commonly associated with DAOs in general.

In contrast to the broad authority governance protocols typically have with respect their treasuries, they typically have limited authority with respect to the underlying smart contracts of the protocol, which often contain immutable code that was solidified at the launch of the governance protocol. This limited authority does not mean that the original developers retained such control. In fact, the keys necessary to make broad changes to the protocol code and the operations its smart contracts perform are typically burned as part of the governance protocol’s activation or, if not burned, then transferred into the control of the DAO. This establishes the trustless nature of the protocol and is one of the key innovations made possible by blockchain technology.

As a result, even though both the treasury and protocol governance proposals are accessible through the governance tokens interaction with the governance protocol, the widely divergent activities and clear delineation between treasury proposals and protocol proposals suggests the possibility that many DAOs could actually be comprised of two distinct entities. 55 While significant interaction between the two would be indicative of a common purpose and necessitate a singular DAO entity, if a DAO’s facts and circumstances truly demonstrated two distinct entities, then the possibility of “siloed” entity structures should be considered. 56

Potentially Automated Tax Calculation

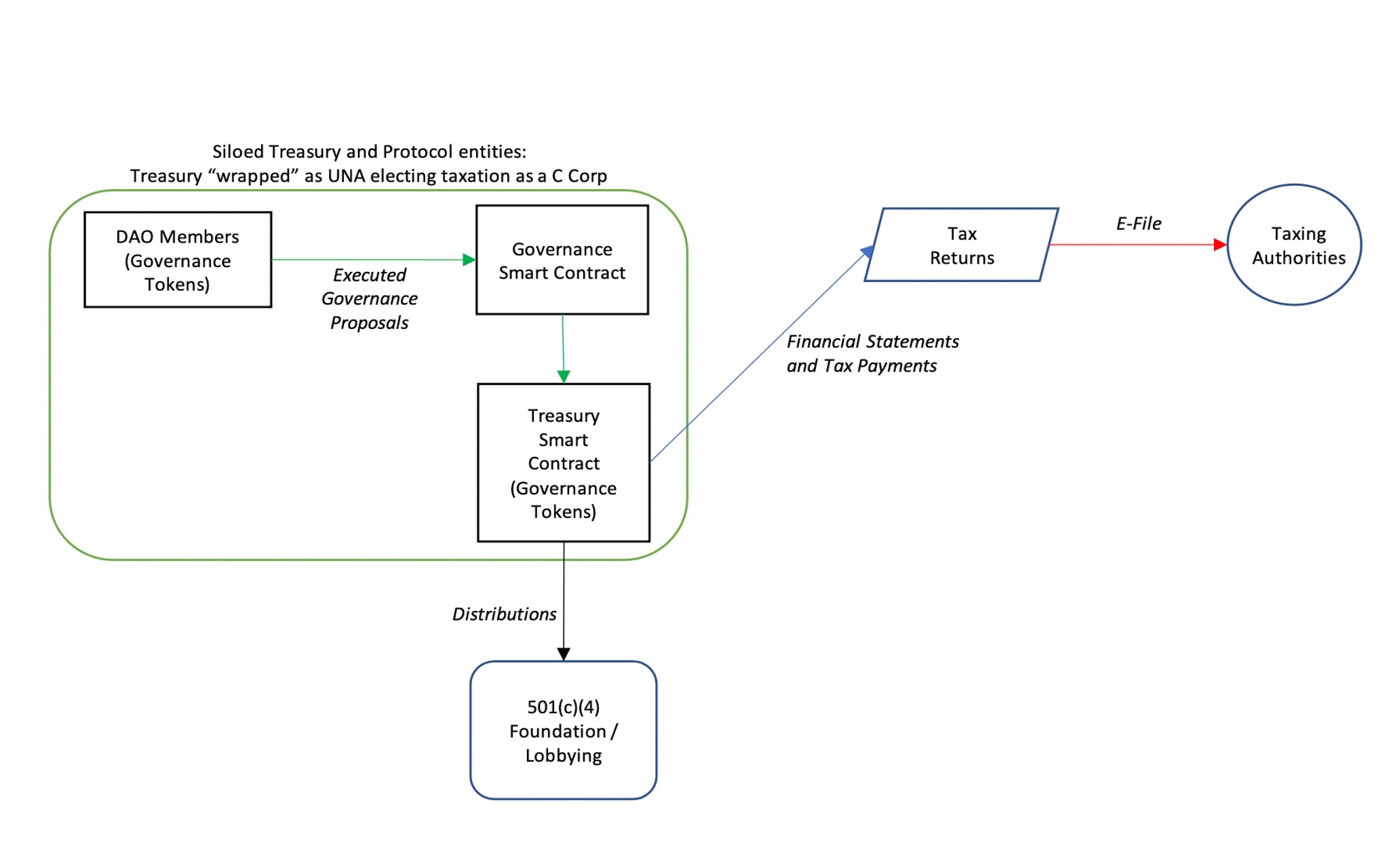

The calculation of tax could be written into the smart contracts at a 21% rate calculated on any disposition of treasury tokens (e.g., treasury diversification sales, token swaps with other DAO treasuries, a hard fork of the governance token or to deposit the funds in a wallet of 501(c)(4) entity associated with the DAO), which could be converted into stablecoins and deposited in the entity’s wallet for the purpose of paying taxes. 57

By writing the 21% rate into any treasury transaction that would result in the recognition of income tax, the DAO would not need to authorize specific proposals to elect to pay taxes, it would be automatic to any taxable event that gave rise to income tax obligations on the treasury tokens, including proposals enacted through governance. In the event the 21% withholding ended in a surplus, the terms of the entity would dictate that the overages be returned to the treasury. 58

In the proposed structures, the entity would be paying income tax in a situation where not only was income tax not being paid previously, but where a clear taxpayer or obligation to pay income tax had yet to be definitively established. As the proposed entity structures results in dominion and control of the treasury assets, they establish a clearly identifiable and appropriate taxpayer for income tax purposes.

Practical Considerations for the Payment of Taxes by UNAs

An eligible entity can utilize Form 8832 to elect its classification for federal tax purposes as a corporation, a partnership or an entity disregarded as separate from its owner. 59 Associations are an eligible entity taxable as a corporation by election and although subject to acceptance by the IRS, Form 8832 is generally considered a pro forma filing. 60 Although there are limitations on when an election can be made, late filing procedures are fairly generous and in the case of the proposed entities, not necessary because Form 8832 would be filed as part of the registration as an UNA. 61

It should be noted that there is a divergence of opinion within many DAO communities over whether DAOs should fundamentally be subject to taxation on any level, taxed as flow-through entities with member’s responsible for paying the income tax associated with the DAO or taxed as a C-Corp with the entity responsible for the payment of taxes at the entity level and members responsible for the payment of taxes for any distributions on their personal returns. 62 Although a for-profit DAO would have to determine what federal tax classification best serves its members, a not for-profit DAO would have no, or negligible, member distributions and the benefits of taxable entity around the treasury discussed throughout this analysis provides amble justification for why it is beneficial for the treasury to be taxed as a C-Corp.

Proposed Entity Structures

As the facts and circumstances of each DAO are unique, there is no singular solution to the question of entity structure.

The key goals of any DAO entity structure should include the following:

- Limit the liability of developers, users and members of DAOs;

- Create a taxpayer capable of paying taxes within the United States for any taxable transactions, especially those involving the DAO Treasury;

- Maintain decentralization by limiting the scope of operations of any individual entity;

- Be consistent with any assertions utilized in other regulatory compliance responsibilities;

- Avoid any reporting obligations under the CTA with respect to underlying governance token holders;

- Promote the availability of trustless and disintermediated transactions wherever possible; and

- Minimize the risk of imputed ownership by governance token holders of the DAO Treasury tokens.

The following section describes two high level applications involving the UNA for entity structures before concluding this analysis with suggested clarifications to the existing law that would assist DAOs in utilizing the UNA as an entity structure. A subsequent publication will follow that contains practical application of the steps necessary for a DAO to utilize these structures under existing law and how a DAO could design its smart contracts to execute the requirement in a trustless and on-chain manner. 63

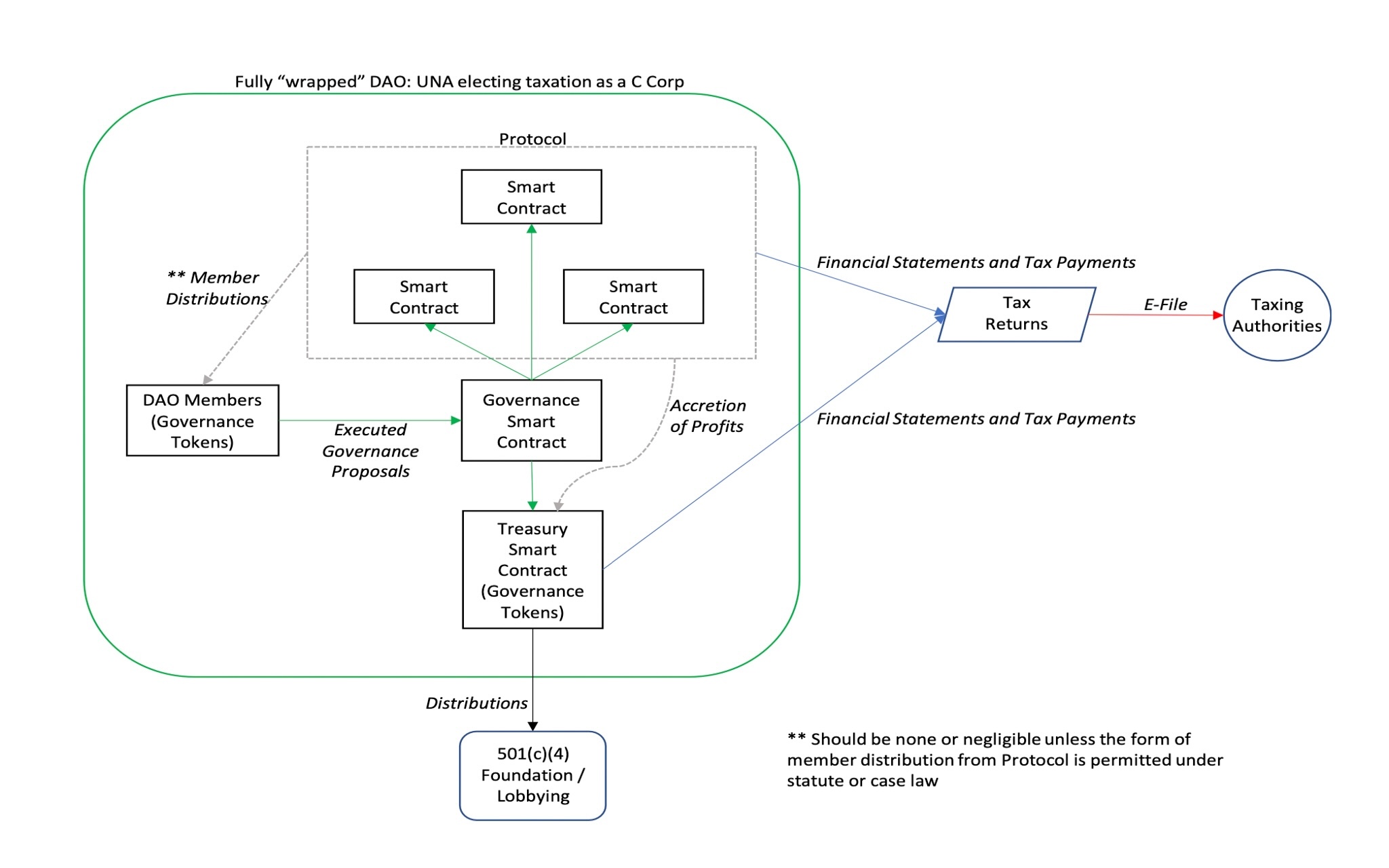

DAO as a Fully “Wrapped” UNA Electing Federal Taxation as a C-Corp

The minimal formality surrounding member requirements provides a significant advantage to utilizing a UNA for DAOs that have already launched their governance protocols. As participation in the DAO can be inferred through conduct, a validly executed governance proposal that was communicated to the membership would provide a mechanism to enact an entity structure that would limit member liabilities.

As a UNA, the DAO would be able to open a bank account, sign contracts, file tax returns, pay employees and in general, meet the requirements of existence to interact as an entity.

Additionally, distributions from the treasury made as part of grant proposals or to fund possible 501(c)(4) foundations or lobbying entities would allow DAOs to utilize these tax-exempt entities as additive structures in service of their not-for-profit purpose. 64

The potential risks to this structure are that any distributions of profit could result in a challenge to the liability limitations and any future change in categorization of not-for-profit intent or entity classification as a result of changes in law would include the complications of the treasury’s locked in value at that time.

However, with minimal clarifications and modifications to the UUNAA as adopted by the states, the UNA entity form could easily become the most appropriate and complimentary entity structure for DAO operations (see Chart 4). 65

DAO with “Siloed” Protocol and Treasury Entities

The benefits of a “siloed” entity structure would allow for the treasury to fully “wrap” itself in a UNA, while allowing the protocol to decide between staying regimeless, “wrapping” itself in a UNA or utilizing an LLC structure, as appropriate to its facts. 66 This would allow a certain measure of certainty to DAOs because keeping the treasury and the protocol separate allows more flexibility to adopt to future changes in law or member decisions making regarding operation. If a fully “wrapped” DAO organized as not-for- profit were to decide that it wished to engage in for-profit activity in the future, the existence of the treasury within its entity structure could result in complications. However, if the treasury and protocol were distinct entities, the treasury would be able to maintain its organizational structure independent of any decision made by the protocol (see Chart 5).

The risks of the “siloed” structure would be the same as a DAO fully “wrapped” in a UNA (that the determination of impermissible member benefit would place the limited liability protections of members at risk), with the additional complexity of having its justification for two separate entities challenged and any tax avoidance concerns resulting from the “siloed” entities potentially being filed in different taxing jurisdictions.

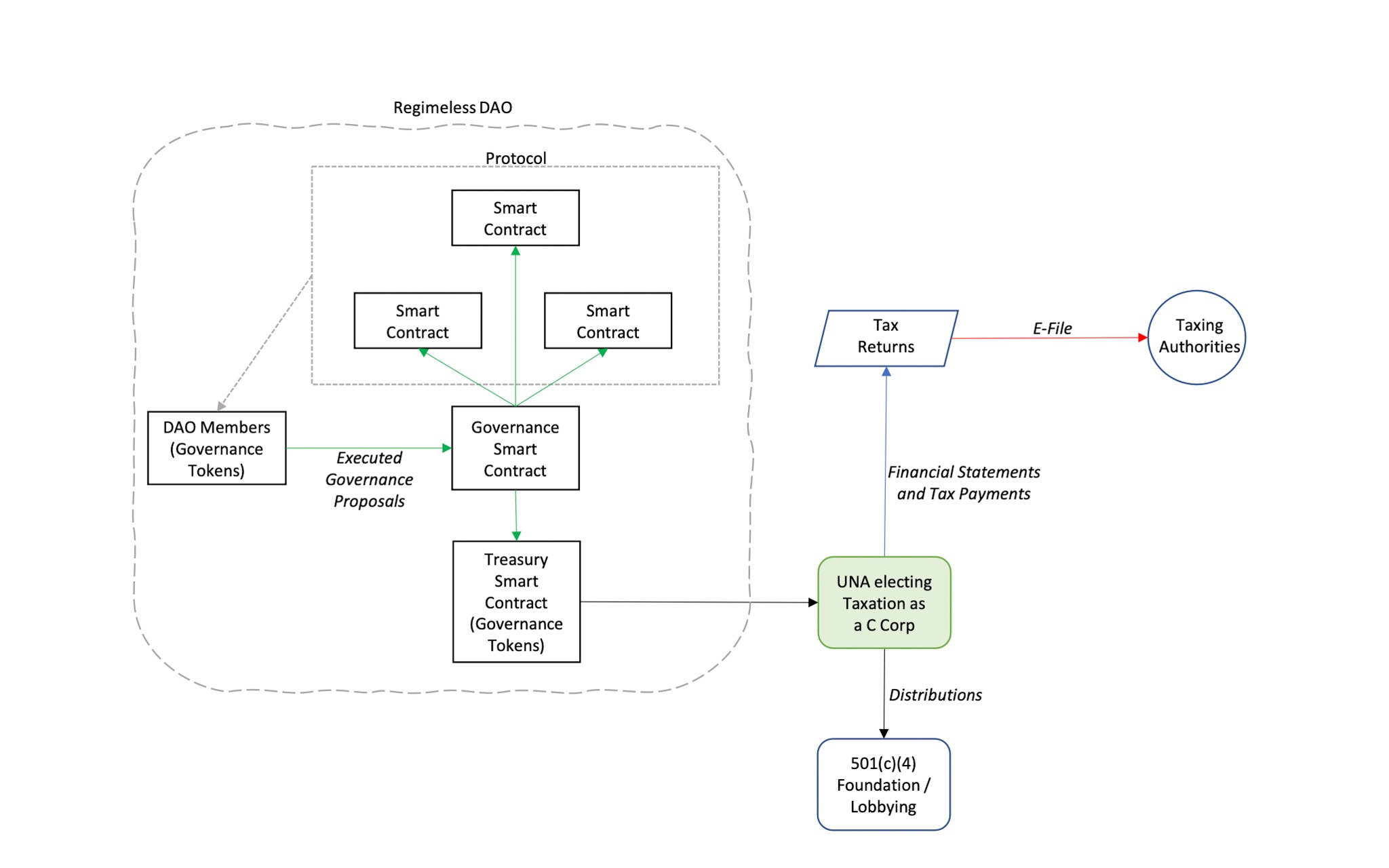

The treasury entity would allow for utilization of the 501(c)(4) foundation/lobbying entities and remit taxes in the same manner as the fully “wrapped” DAO (see Chart 6).

However, the protocol entity would need to evaluate the most appropriate entity classification for its facts and circumstances.

An alternative application of the “siloed” entity structure could provide a solution to a regimeless DAO’s inability to file tax returns. Although the absence of a legal entity over the DAO would leave segments of the DAO uncovered, most of the risk associated with DAO operations is contained within the operation of the treasuries and a “siloed” entity structure around distributions of the treasury would provide a mechanism for filing and paying taxes, limitation of some of the liabilities and facilitate the distribution of funds to establish grant programs, foundations or lobbying entities (see Chart 7). 67

Accordingly, a UNA electing taxation as a C-Corp could be created that exerts dominion and control over the smart contracts associated with treasury distributions of validly enacted governance proposals. Although the articles of association and bylaws for the entity could be strictly written such that the entity was required to execute the proposals as enacted by the governance (such that they were compliant with the law), the dominion and control exercised by such an entity would resolve any concerns over the assignment of income, thereby creating an appropriate taxpayer for the purpose of filing and paying taxes associated with treasury distributions.

Although this proposed entity does not resolve many of the issues related to a regimeless DAO, it does represent a good faith effort to resolve a regimeless DAO’s inability to file and pay taxes regarding operations of its treasury. Additionally, this proposed structure requires minimal alterations to existing tax planning and could easily be modified to conform with any future regulatory and legislative requirements applicable to DAOs.

Conclusion

Until such a time that comprehensive legislation and regulatory guidance exists specific to DAOs, many of the issues arising from DAO entity structural decisions cannot be definitively resolved. Although the smart contracts and functionality giving rise to the DAO exist solely on the internet and an argument can be made that their operations would be excluded from U.S. tax obligation, significant ties to the U.S. and the dominion and control over DAO treasuries establish a need for U.S. tax obligations to be met. Absent the adoption of a U.S. entity structure or a legal offshore structure, the developers and members of a DAO are at risk of potentially being (i) restricted from engaging in operations, (ii) held liable for any harm resulting from DAO activities and (iii) held liable for income tax liabilities associated with a protocol’s operation and issuances of a treasury’s governance tokens.

As most DAOs are designed as nonprofits and engage in not-for-profit activities, our analysis suggests that the UNA entity structure could be adopted by a variety of DAOs to limit liability and meet their tax obligations in some form. However, such structure may be less flexible than what DAOs seeking to distribute profits to members require. While in such cases alternative “siloed” structures utilizing UNAs could be available, the complexity and limitations associated with these structures could be alleviated by clarification from federal and state governments formally recognizing a UNA form for DAOs. Additionally, the law must ultimately distinguish between impermissible member benefit from members of the DAO being compensated for the services provided in benefit of the protocol and its not-for-profit purpose.

Federal and state legislatures should recognize that expansion of the UNA to DAOs would facilitate the payment of taxes, provide clarity in legal treatment and encourage a developing technology that would benefit their constituents. Limitations on tax exemptions would discourage misuse of the expanded DAO construct, and federal tax revenues would likely increase significantly as a result. In addition, it would keep these organizations under the direct supervision of U.S. regulators, increase U.S. tax revenues, and foster further development of this emerging technology in the United States. Beyond the recognition of DAOs, comprehensive legislative reform must eventually include an overall reduction of the tax burden outlined in this memo or the developing technology associated with DAOs and all of its benefits will migrate to more progressive jurisdictions.

While the industry awaits legislative action regarding DAO entity forms, there is still much benefit for DAOs in utilizing the existing UNA entity structure because it allows DAOs to evolve within the U.S. regulatory environment as good faith participates and demonstrates a willingness to pay taxes prior to any enforcement actions or targeted legislation assessing taxes.

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

Miles Jennings is General Counsel of a16z crypto, where he advises the firm and its portfolio companies on decentralization, DAOs, governance, NFTs, and state and federal securities laws. Previously, he was a partner at Latham & Watkins where he cochaired its global blockchain and cryptocurrency task force. He was previously a partner at Latham & Watkins. David Kerr is the Principal of Cowrie, where he uses 10 years of experience in tax strategy, financial accounting, and risk advisory in the industries of gaming, telecommunications, and technology-driven online sales platforms to assist clients with risk mitigation strategies on developing web3 issues.

↩ -

A detailed examination of all the possibilities for the protocol entity is beyond the scope of this analysis, but future publications will expand on how the principles of this proposed structure can widely be adapted by DAOs and tailored to their specific requirements. ↩

-

See generally Aaron Wright, The Rise of Decentralized Autonomous Organization: Opportunities and Challenges, Stanford Journal of Blockchain Law & Policy: Vol. 4 No. 2 (June 30, 2021), available at https://stanford-jblp.pubpub.org/pub/rise-of-daos/release/1 (for a detailed analysis of DAO organizational structures and developments). ↩

-

IRS Statements and Announcements, Internal Revenue Service, Witten Testimony of Charles P. Rettig, Commissioner Internal Revenue Service before the Senate Finance Committee on the IRS Budget (June 8, 2021), available at https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/written-testimony-of-charles-p-rettig-commissioner-internal-revenue-service-before-the-senate-finance-committee-on-the-irs-budget (for a discussion of the IRS’ proposed budget and alignment with the President’s Legislative Proposals). ↩

-

Internal Revenue Service, The Agency, its Mission and Statutory Authority, available at https://www.irs.gov/about-irs/the-agency-its-mission-and-statutory-authority (last visited Oct. 17, 2021). ↩

-

The IRS has largely remained silent regarding the taxation of digital assets and has even prohibited taxpayers from requesting private letter rulings for clarification of certain tax issues related to digital assets (see Rev. Proc. 2021-3, Section 3: Areas in Which Rulings or Determination Letters Will Not be Issued, (98) Sections 1001 and 1058: “Whether a taxpayer recognizes gain or loss on the transfer of virtual currency in exchange for a contractual obligation that requires the return of identical virtual currency to the taxpayer or on the transfer of identical virtual currency to the taxpayer in satisfaction of the contractual obligation”).

Although the IRS has expressed its opinion that virtual currency should be treated as property, it has only done so through a 2014 Revenue Notice establishing that position and a 2019 Revenue Ruling applying its interpretation to two very limited tax situations. Revenue Notices and Revenue Rulings are considered “published sub-regulatory guidance” and neither are considered controlling authority for legal purposes (although Revenue Rulings have a history of being afforded slightly more persuasive authority by the courts in situations where the facts are analogous to the Ruling). Although a taxpayer can rely on the publications as authoritative, if a taxpayer were to take a contrary position to the IRS, it is the IRS’s obligation to prove its position in court. (For further discussion of “published sub-regulatory guidance” see generally, Matt Lerner, et al., To Rely On or Not to Rely On? Sub-Regulatory Tax Guidance in Turbulent Times, Tax Executive: The Professional Journal of Tax Executives Institute (Feb. 2, 2021), available at https://taxexecutive.org/to-rely-on-or-not-to-rely-on-sub-regulatory-tax-guidance-in-turbulent-times/.

The IRS’s position that virtual currency should be taxed as property is regarded as fairly unassailable given the IRS’s authority to interpret existing tax law and the established principles of income recognition, but the IRS has not clarified which specific IRC codes apply to virtual currency and a number of reasonable interpretations are available to taxpayers for issues extending beyond simply the treatment of virtual currency as property. ↩ -

The IRS enforcement and compliance efforts related to virtual currency include summonses issued to taxpayers, third parties and “John Doe” summonses compelling entities to share user data. Additionally, over 10,000 letters have been sent to individual taxpayers specifically informing them of their possible taxation reporting requirements for digital asset activities. See generally, Alison Frankel, Crypto user asks 1st Circuit to curtail IRS collection of records, Reuters Legal News (Oct. 6, 2021), available at https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/crypto-user-asks-1st-circuit-curtail-irs-collection-records-2021-10-06/. ↩

-

On June 8th, 2021, U.S. IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig alluded to the existing limitations in statutory authority faced by the IRS when appearing before the Senate Finance Committee. When questioned on the IRS’s ability to collect information on cryptocurrency transfers, Commissioner Rettig stated, “I think we need congressional authority. We get challenged frequently, and to have a clear dictate from Congress on the authority for [the IRS] to collect that information is critical.” David Lawder, U.S. IRS chief asks Congress for authority to collect cryptocurrency transfer data, Reuters Legal News (June 8, 2021), available at https://www.reuters.com/business/us-irs-chief-says-needs-congressional-authority-cryptocurrency-reporting-2021-06-08/. ↩

-

26 USC §6724(d)(1).

Examples of information returns include trade or business payments (contained on Form 1099-NEC and 1099-MISC), compensation for services (contained on Form W-2), broker sales (contained on Form 1099-B), interest payments (contained on Form 1099-INT) and dividend payments (contained on Form 1099-DIV). Pass-through entities such as partnerships and S-corps are required to report taxable income (contained on Schedule K-1). ↩ -

American Families Plan Tax Compliance Agenda, U.S. Department of the Treasury (May 2021), available at https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/The-American-Families-Plan-Tax-Compliance-Agenda.pdf. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

See Abraham Sutherland, Research Report: Tax code section 5060I and “digital assets”, Proof of Stake Alliance (Sept. 17, 2021), available at https://www.proofofstakealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Research-Report-on-Tax-Code-6050I-and-Digital-Assets.pdf. ↩

-

IRC Section 6050I and Form 8300 are collected by the IRS, but their purpose is to monitor money distributions to detect criminality. The late 1990’s and early 2000’s saw a concerted effort by the federal government to eliminate the protections afforded taxpayers in the distribution of the information contained on Form 8300, which had previously been protected under the disclosure rules for tax returns. Through an expansion of the BSA and the permanent provisions of the Patriot Act, the information contained on Form 8300 was made available to various federal and even state enforcement agencies. Irrespective of any benefit or harm from the expansion of the $10,000 reporting requirement through the proposed amendment of IRC Section 6050I in the infrastructure bill, it is implausible that the costs associated with maintaining and enforcing such a program would result in a budget surplus. See generally, Internal Revenue Service, Internal Revenue Manuals, Part 4 - Examining Process, Chapter 26, Bank Secrecy Act, Section 10, Form 8300 History and Law (March 23, 2020), available at https://www.irs.gov/irm/part4/irm_04-026-010. ↩

-

For example, in an effort to expand the percentage of income related to digital assets reported by third parties to the IRS, the amendment to IRC Section 6045 set forth in the proposed infrastructure bill attempts to address the most obvious justifications for why a taxpayer would be excluded from a reporting requirement (i.e., that the activity being performed is not included in the reporting requirements as described by statute). As applied to the target of the proposed legislation, the argument would be that because IRC Section 6045 does not clearly define the underlying activity as included, any 1099-B and 1099-DIV reporting obligations that would otherwise be required do not meet the definition of a “broker or barter exchange.” However, the pervasiveness of that justification for the inapplicability of tax reporting requirements is a product of its ease and application for broadly addressing the issue, not that it is the only available justification for why the tax reporting requirements do not apply. Accordingly, if digital assets were to become specifically included in IRC Section 6045, it would not necessarily mean the reporting requirements were universally applicable to all digital assets. Rather, every U.S. taxpayer possibly effected would need to perform a review of its facts and circumstances to assess the applicability of the changed law.

Given the broadness of the expanded language pertaining to broker transfers, it is conceivable that many traditional financial service transactions not previously required to make 1099 disclosures would fall under the language proposed in Section 6045A(d) related to transfers of digital assets. Whereas, given the term broker as contained in Section 6045(c)(1)(C) and modified in the proposed amendment that “any person who (for a consideration) regularly acts as a middleman with respect to property or services” and Section 6045(c)(1)(D) that “any person who (for consideration) is responsible for regularly providing any service effectuating transfers of digital assets on behalf of another person,’’ establish a requirement of consideration to be included as a broker, many DeFi protocols and DAOs would likely be excluded from the reporting requirements do to an absence of consideration within their functionality. See generally, 26 USC §6045, 26 USC §6050I and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, H.R. 3684,117th Cong. § 1 (2021), available at https://www.epw.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/e/a/ea1eb2e4-56bd-45f1-a260-9d6ee951bc96/F8A7C77D69BE09151F210EB4DFE872CD.edw21a09.pdf.

In addition, the proposed expanded reporting requirements may also not be applicable to many DeFi protocols due to the functionality of their smart contracts. As smart contracts typically allow for the disintermediation of transactions, many of the existing DeFi protocols facilitate peer-to-peer operations. An example of this can be found in decentralized exchanges. As opposed to intermediated/centralized exchanges, decentralized exchanges utilize an atomic swap, which is a direct exchange of digital assets, in this case tokens. “Atomic swaps” utilize a hash time lock to limit the period on which transactions can occur before canceling and allows the exchange of digital assets to occur without the involvement of a third-party. Although users of a decentralized exchange that swap tokens and contribute tokens to liquidity pools would still report the income from those transactions on their tax returns, the decentralized exchange could potentially avoid reporting requirements on the peer-to-peer exchange by benefit of the disintermediated nature of the transaction because there is no third-party to make subject to the reporting requirements. However, if the proposed law were interpreted broadly to apply to developers of protocol smart contracts, a significant number of on-chain transactions may need to be reported. The utility of such reporting is highly questionable given that such transactions are on-chain and therefore, already publicly available in the case of most major blockchains (i.e., Bitcoin, Ethereum, etc.). An expansion of the government’s utilization of on-chain records presents an opportunity for more effective oversight not reliant on overly broad and invasive informational disclosures. ↩ -

Internal Revenue Bulletin 2014-16, Notice 2014-21 (April 14, 2014), available at https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-14-21.pdf. ↩

-

Id. See also, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Interpretative Guidance FIN-2013-G001, Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Person Administering, Exchanging, or Using Virtual Currencies (March 18, 2013), available at https://www.fincen.gov/sites/default/files/shared/FIN-2013-G001.pdf. ↩

-

The IRS generally defines airdrops as “a means of distributing units of a cryptocurrency to the distributed ledger addresses of multiple taxpayers.” Internal Revenue Bulletin 2019-44, Rev. Rul. 2019-24, pg. 1004 (Oct. 28, 2019), available at https://www.irs.gov/irb/2019-44_IRB. However, the term is utilized more specifically in the industry to describe situations where a company gives away cryptocurrency or tokens.