A Legal Framework for DAOs (Part III)

This post was originally published in April 2024 as part of Miles Jennings and David Kerr's series on domestic legal entity frameworks.1

If you'd prefer to read this article in PDF format, click here.

DISCLAIMER: This analysis should not be construed as legal, business, tax or investment advice for any particular facts or circumstances and is not meant to replace competent counsel. None of the opinions or positions provided hereby are intended to be treated as legal advice or to create an attorney-client relationship. This analysis might not reflect all current updates to applicable laws or interpretive guidance and the authors disclaim any obligation to update this paper. It is strongly advised for you to contact a reputable attorney in your jurisdiction for any questions or concerns. The invitation to contact is not a solicitation for legal work under the laws of any jurisdiction. Please see http://a16z.com/disclosures for more information.

Introduction:

The blockchain technology underpinning web3 is fundamentally changing how the internet can be used, enabling the creation of decentralized digital services and providing a settlement layer capable of nearly instantaneous transfers of value. What began as a single decentralized blockchain network has grown into the decentralized products and services known as “DeFi” and is now expanding to create a version of the internet built on decentralized public infrastructure whose maintenance is not dependent on the powers or interests of an individual or primary leadership group. 2 Although the realization of blockchain’s potential is well underway, it remains to be seen what role the United States will have in this innovation.

Alarmingly, an increasing number of indicators portend a future where the United States falls behind in this developing sector, with growth in web3 developers outside the United States now outpacing growth within it.3 U.S. projects have overwhelmingly offshored the decentralized autonomous organizations (“DAOs”) tasked with overseeing the networks and protocols originally developed in the United States. Much of this exodus can be traced to regulatory uncertainty stemming from a lack of guidance and an inconsistent application of U.S. securities laws, as well as a lack of clarity in the available domestic legal entity structures for the organizations themselves. Despite these trends, the historical stability of the U.S. legal system, the number of developers in the United States and the need for a system where individuals can control their own data all uniquely position the United States to lead in web3 and benefit from supporting its growth.

Various members of Congress and even the White House have already contributed to this effort with several promising legislative proposals and an executive order.4 However, regardless of whether web3 achieves success at the federal level, the United States will not continue as a jurisdictional center for the developing technology unless state legislatures support the use of domestic legal entity structures by DAOs formed around network and smart contract protocols. Part I 5 and Part II 6 of The Legal Framework for Decentralized Autonomous Organizations series provided a detailed analysis of the challenges DAOs currently face with respect to adopting legal entity forms (e.g., attaining limited liability, the circumstances resulting in informational reporting of members and the payment of taxes). Part II ultimately concluded that in a majority of circumstances, the unincorporated nonprofit association (“UNA”) provides the best domestic entity structure template for solving substantially all the legal entity-related issues facing DAOs.

As a general principle, state UNA laws were designed to be particularly flexible in accommodating ad hoc structures and significant informalities, making the UNA well-situated to accommodate decentralized organizations. While this flexibility allows for many types of DAOs to organize as UNAs, existing UNA statutes do not provide clarity as to whether they were intended to be utilized for this purpose and the degree to which UNA laws can be relied upon as a long-term solution creates uncertainty in planning. As a result, the UNA entity structure has not widely been adopted by DAOs.

However, many states are enthusiastic about supporting decentralization and are actively looking to implement legal entity forms that support the development of web3.7 Pairing existing legislative efforts with the most effective legal entity template presents a tremendous opportunity to create impactful legislation that would relieve state jurisdictions of having to apply laws to activities not contemplated when they were created, allow for the introduction of effective regulation within the legislation and provide clarity to the entity selection process for decentralized organizations.

This Part III proposes to do just that by introducing the Model Decentralized Unincorporated Nonprofit Association Act (“Model DUNAA”) for consideration by U.S. states. Adoption of the bill by a state would establish the decentralized unincorporated nonprofit association (“DUNA”) as a category within existing business organization codes for use by decentralized organizations.8 States adopting a DUNA entity form based on the Model DUNAA stand to benefit in several ways. First, adoption would provide states with the legal infrastructure necessary to promote innovation in web3. Second, it would make such states an attractive home for international organizations capable of significant growth and economic benefit (particularly in the collection of tax revenue). Third, by participating in the formation of the rules, the states will be able to meaningfully address specific issues necessary to ensure consistency with their existing laws and when necessary, have disputes resolved in the courts of their legal system.

Principles of the Proposal

A DUNA would be an electable form of unincorporated nonprofit association similar in construction to the Uniform Unincorporated Nonprofit Association Act (“UUNAA”) contemplating the organizational requirements of decentralized organizations. As detailed herein, the construction of the Model DUNAA has been undertaken in accordance with the following principles:

- Minimize Deviations from Existing Laws – The Model DUNAA substantively deviates from existing UNA laws only where necessary to address operational considerations or provide additional clarity. While many changes were made to the default language of the UUNAA and RUUNNA to provide additional detail in how the Model DUNAA would likely be utilized by decentralized organizations – these changes provide no additional benefit from what could already be attained under existing UNA laws.

- Minimize Conflicts of Law – The Model DUNAA seeks to minimize potential conflicts with existing state laws. It does not encroach on any existing legal entity forms and it is not a default structure, rather it must be elected and conform to the laws of an adopting state and the act itself. As the Model DUNAA contains restrictions on distributions and minimum membership levels – it presents a clearly defined use case for when it should be utilized.

- Forgo Special Treatment – The Model DUNAA is technologically neutral and does not provide organizations electing to form as DUNAs with special treatment under the law or treat particular forms of technology in an inconsistent manner. States wishing to adopt the Model DUNAA must consider any existing UNA laws and relevant existing statutes (i.e., agency laws, registration requirements, books and records requirements, service of process, etc.) to ensure that their DUNA laws are consistent with existing law.

- Suitability for Decentralized Organizations – The Model DUNAA is tailored specifically for use by decentralized organizations and contemplates a baseline structure that does not include a management function, instead it allows for the selection of administrators with limited authorization to perform specific tasks authorized by the membership. Implicit in this concept is the idea that the success of decentralized organizations is not dependent on the managerial efforts of an individual person or group of persons. As a result, DUNAs are best suited for organizations formed for the purpose of administering the affairs of an autonomous blockchain network, smart contract protocol or equivalent purpose, and not well-suited for organizations that are reliant on traditional management structures and hierarchies.

- Maximize Future Structuring Options – The regulatory and legal regimes applicable to blockchain technology and other technology sectors are in a period of flux. Modernization of existing laws is a necessity, but any such efforts should prioritize flexibility given the rapidly evolving development of blockchain technology and its use cases. The Model DUNAA contemplates the necessity of organizations being able to convert or merge into different structures based on changes in law or changes in operation. This flexibility will provide existing organizations certainty that their selection of the DUNA will not restrict their ability to keep pace with future changes in the law.

States Considering adoption of the Model DUNAA

A number of states are considering adoption of the Model DUNAA in some form – including California, Texas and Wyoming.

California Assembly Bill 1229 was introduced in the 2023-2024 regular session and was passed from the House Banking and Finance Committee to the House Judiciary Committee.9 From July 2000 through May 2005, the California Legislature performed an extensive inquiry into adoption of the UUNAA, ultimately passing a number of amendments to augment its existing UNA laws.10 As California’s UNA laws are a significant departure from the UUNAA and RUUNAA, particularly in the treatment of for-profit and non- profit organizations, AB 1229 is very dissimilar in presentation from the Model DUNAA proposed herein, as it was drafted as an insert to sit next to California’s existing laws pertaining to unincorporated nonprofit associations.

Texas House Bill 3768 was introduced in the 2023-2024 legislative session and was passed from the House to the Senate.11 It did not receive a vote in the Senate and is expected to be reintroduced in the next legislative session. HB 3768 is substantively similar to the Model DUNAA proposed herein, with differences deriving from conformity to existing Texas law, particularly Chapter 252 of the Texas Business Organization Code governing unincorporated nonprofit associations, enacted in 2003.12

Wyoming Bill SF0050 has passed both the House and the Senate in the 2024 legislative session and is pending signature from the Governor to go into effect on July 1, 2024.13 SF0050 is substantively similar to the Model DUNAA proposed herein, with differences deriving from conformity to existing Wyoming law, particularly Title 17, Chapter 2022, governing unincorporated nonprofit associations enacted in 1993. 14

Background on the Proposal

Unique Characteristics of Web3 Technology 15

In web2, companies build and operate business models designed to capture the value created by the proprietary technology they have developed and their proprietary network of users. In web3, programmable blockchains make it possible for web3 companies to develop technology that can be utilized as public infrastructure, on top of which anyone can build and offer digital services.

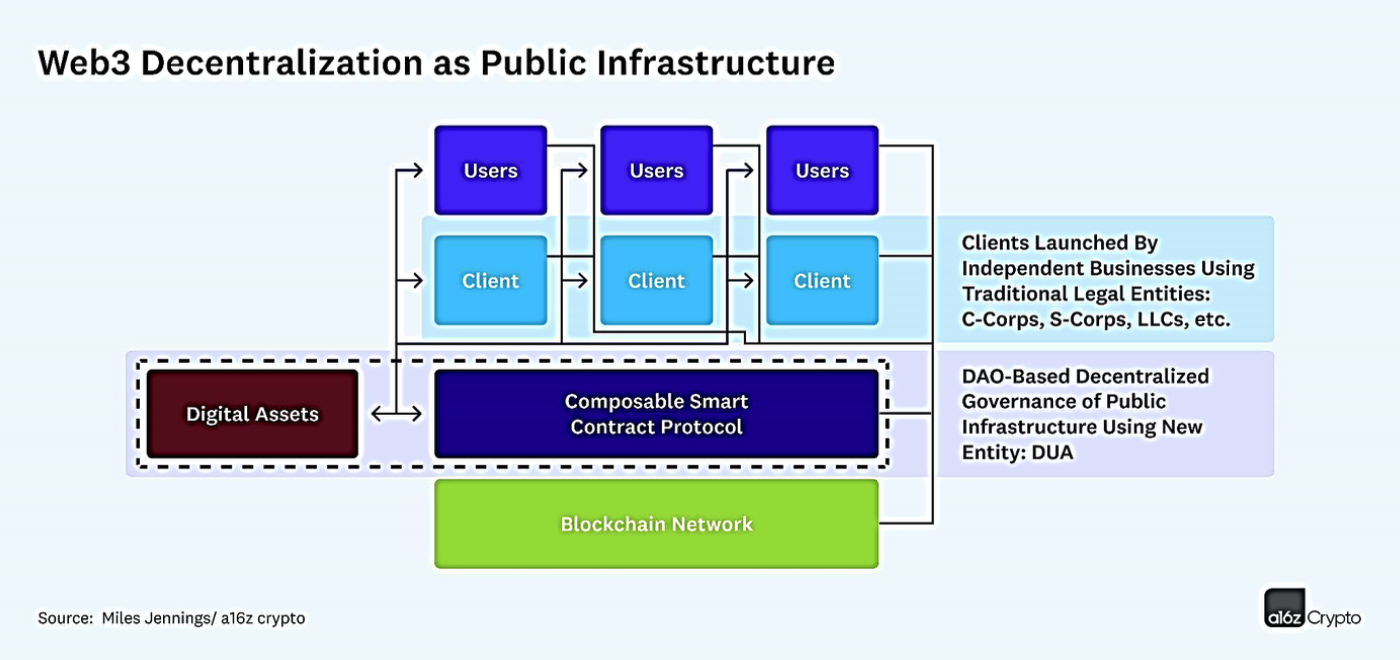

The underlying architecture for web3 is comprised of several layers, which are reflected in the image below: 2. A decentralized and composable smart contract protocol (e.g., Uniswap, Compound, Aave, etc.) deployed to a blockchain that enables programmatic execution of promises and commitments (collectively, with the Blockchain Layer, the “Protocol Layer”). 3. Proprietary and independent clients that act as a gateway for users to interact with the Protocol Layer (e.g., websites like app.uniswap.org, app.compound.finance, app.aave.com, etc.) (the “App Layer” or “Client Layer”).

The underlying technology of blockchain networks and smart contract protocols alone do not give rise to a need for new legal entity structures. For example, there are several open source web1 protocols that are still in use today (e.g., https, smtp, ftp, etc.) that do not require entity structures. Similarly, blockchain networks like bitcoin and ethereum, likely do not require entity structures. However, the picture becomes more complex in situations where a blockchain network or smart contract protocol both conveys governance rights over its underlying technology to the holders of the native digital assets of such technology and gives those holders control over income generated by the technology that does not directly accrue to the original creator or any other readily identifiable taxpayer.

Typically, the decentralized organizations overseeing such technologies are composed of the holders of governance tokens, which are distributed freely to users of a given blockchain or protocol and community participants, as well as to the company or group that developed the technology. The governance tokens enable the members to participate in the operation of the decentralized organization by suggesting and voting on proposals. A significant portion of governance tokens are often also retained by a treasury that is controlled by governance. These tokens can be used to fund the decentralized development and growth of the decentralized ecosystem surrounding the blockchain or protocol. For example, treasury tokens are often used to incentivize and reward protocol user activity (most often through staking or liquidity mining) and by funding ongoing decentralized development efforts, such as the creation of applications to run on top of the blockchain or data analytics tools and new clients/front-end websites for the protocol. These decentralized development efforts are often undertaken by independent third-parties utilizing separate legal entity structures. Additionally, taxable income can be generated from treasury-related activities, including treasury diversification efforts and investment activity.

As a result of these features, three core problems arise for decentralized organizations overseeing blockchain networks and smart contract protocols that jeopardize their viability in web3:

- they do not have legal existence and are therefore unable to contract with third-parties for ongoing development efforts, easily engage legal or financial advisors (e.g., accountants and bookkeepers) or open bank accounts as required for non-crypto transaction;

- they are unable to pay taxes; and

- they potentially expose members to liability.

An appropriate legal entity structure could address all three of these issues and is therefore critical to support the functioning and decentralization of web3.

The importance of decentralization in web3 cannot be understated. The decentralized ownership and operation of the blockchain networks and smart contract protocols of web3 means that such networks and protocols can maintain credible neutrality 16 and function more like public infrastructure than proprietary technology platforms operated by monolithic corporations. This infrastructure can then be built upon by proprietary businesses utilizing traditional entity forms. For example, consider an App Store owned and operated by the public and populated with applications created by independent businesses.

Ultimately, the decentralized organizations of web3 will function much like a city or a homeowners association, administering the affairs of the network or protocol, as opposed to a technology conglomerate building on proprietary systems. This decentralization will also lead to more stakeholder capitalism 17, reduced censorship, greater diversity, enhanced transparency and the promotion of the safety and security of web3 systems. 18

Problems with Existing Legal Entity Structures

The propagation of DAOs has been accompanied by significant uncertainty regarding what type of legal entity a DAO may be eligible to use under applicable state law. As outlined in Part I and Part II, the most common domestic U.S. entity legal structures (corporations, partnerships and co-ops) are all unsuitable for use by network and protocol DAOs.

Accordingly, DAOs generally either do not make use of a legal entity (an “entityless” structure) or they adopt an ownerless foreign foundation structure. The entityless structure leaves all three of the issues facing DAOs discussed above (e.g., no legal existence, no ability to pay taxes, and potential unlimited liability) unresolved. The foreign foundation structures solve these three problems, but have their own significant issues, including (i) they require real-world human control, which limits the extent to which they can be truly trustless and decentralized, (ii) they are extremely complicated, costly and difficult to set up, and (iii) they subject the DAO to uncertain tax treatment and could ultimately be challenged by many different jurisdictions. In addition, the use of foreign foundations means that economic activity relating to networks and protocols originally created in the United States is being shipped offshore rather than retained within it.

Unincorporated Associations

Unincorporated associations are a frequently misunderstood topic in legal entity discussions as the term holds a variety of meanings depending on context. A fairly typical state definition of an unincorporated association is “an unincorporated group of two or more persons joined by mutual consent for a common lawful purpose, whether organized for profit or not.”19 This wide definition applies to any entity that is not incorporated (e.g., entities besides C Corporations, S Corporations, Nonprofit Corporations and Cooperatives generally) or comprised of more than a single person (e.g., a sole proprietorship). 20

Until fairly recently, it was common practice to refer to general partnerships, joint ventures and limited partnerships collectively as unincorporated business associations. 21 These unincorporated business associations shared a commonality of unlimited liability for some or all its members, in contrast to the limited liability available to incorporated entities. However, the past seventy years have seen a seismic shift in the treatment of unincorporated associations, as evidenced by the creation of hybrid entity forms like the limited liability partnership, limited liability corporations, limited cooperative associations and UNAs, which in many ways provide the same legal protections and at times, the same legal standing as incorporated entities.

This change has blurred the historically rigid distinction between incorporated and unincorporated entities, and the relevance of being an unincorporated association became significantly less meaningful, as it is the statutes and case law around these hybrid entity forms that dictate their treatment. For example, while an LLC is an unincorporated association, they are controlled by the state statutes that give rise to the entity form and not the laws pertaining to unincorporated associations generally. 22

As the usage of these hybrid entity forms increased and case law developed that carved out limited but meaningful reductions in historical liability even for participants in general partnerships and joint ventures – the significance of the distinction between incorporated versus unincorporated entity forms diminished such that modern references to unincorporated associations are usually in reference to a specific entity form (e.g., an unincorporated nonprofit association or a for-profit unincorporated association) and not the classification of incorporated versus unincorporated entities generally.

Unincorporated Nonprofit Associations

Under the common law of many states, when two or more persons engage in an endeavor for a purpose other than to operate a business for-profit, the default structure is that of an unincorporated association. Unincorporated associations reflected the nonprofit version of general partnerships and accordingly, have evolved into being called unincorporated nonprofit associations.

Over the past two-hundred years, many jurisdictions have enacted piecemeal statues around unincorporated nonprofit associations granting varying degrees of legal entity status or near-legal entity status to unincorporated nonprofit associations, with the result being a myriad of common law and state statues governing various legal aspects of the entity form across various jurisdictions. In furtherance of its efforts to bring “clarity and stability to critical areas of state law,” the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (“NCCUSL”) promulgated the original Uniform Unincorporated Nonprofit Association Act in 1996 and released a significant revision in 2008 that was last amended in 2011. 23

As discussed in Part I and Part II, the lack of traditional formalities within the UUNAA provides significant flexibility and the UNA entity form meets the primary needs of many decentralized organizations, including network and protocol DAOs, thereby enabling them to attain legal existence, meet their tax obligations and limit member liability. However, the breadth of organizations whose activities could qualify as UNAs and the need for the entity form to be designed extremely broadly to accommodate any number of scenarios presents an obstacle in providing statutory language around internal rules of governance or even placing prohibitions on distributions (e.g., cooperatives can form as UNAs and do allow for distributions).

However, the current breadth of existing UNA laws is not a protection if a jurisdiction were to enact legislation limiting their applicability to certain forms of technology or use cases in the future. Moreover, there are several aspects of the UUNAA that could be improved for decentralized organizations that would benefit from the clarity in having tailored statutory language.

The Model DUNAA seeks to establish an unincorporated nonprofit association entity form properly tailored for decentralized organizations. For states that have already adopted the UUNAA, the Model DUNAA would only apply to a narrow subset of decentralized UNAs. For states that have not adopted the UUNAA, the Model DUNAA provides a limited application of the unincorporated nonprofit associations entity form that could be adopted for decentralized organizations or extended more broadly with the adoption of the UUNAA. 24

Reason for the Proposal

The Model DUNAA seeks to establish an entity form properly tailored for decentralized organizations whose operations are impacted by technological function, including DAOs. As the Model DUNAA is an opt-in form of an unincorporated nonprofit association tailored to the needs of such decentralized organizations, it establishes clear intent on the part of states to provide a pathway for legal existence for such decentralized organizations. In addition, as discussed below under the heading “Description of Proposal,” the Model DUNAA optimizes the unincorporated form for decentralized organizations.

Even though DAOs are widely referenced in describing the need for this law and drive the intent behind it, the Model DUNAA is written as technologically agnostic to accommodate potential changes in technology that could produce new types of decentralized organizations, in whatever form that may take in the future. However, the Model DUNAA is best suited for an organization formed to administer the affairs of an autonomous blockchain network or smart contract protocol. This is because the Model DUNAA eliminates the utilization of a hierarchy of individuals responsible for managing the enterprise (e.g., directors, officers and managers) and only provides for administrator roles with limited authorization to administer specific tasks authorized by the membership. As a result, the Model DUNAA would not be an option for traditional business structures or organizations with centralized management. 25

Given those parameters, it is most appropriate to characterize the DUNA as being a legal entity wrapper for autonomous software that is administered by a DAO or equivalently decentralized structure, rather than as it being a legal entity wrapper for a web3 company.

Description of Proposal

The construction of the Model DUNAA is closely based on the most recently amended version of UUNAA from 2011, with the intention of clarifying the applicability and application of those statues to decentralized organizations. 26

It is constructed as a freestanding body of law that sufficiently provides for the organization and operation of DUNAs whether the enacting state has adopted the UUNAA or equivalently protected unincorporated associations through its case law or statutory modifications to the common law. However, if an enacting jurisdiction has adopted the UUNAA, a significantly leaner version of the Model DUNAA could be enacted than the freestanding form contained herein. Equally important, if a jurisdiction has not adopted the UNA or has already developed significant protections for unincorporated associations through other means, the Model DUNAA can still be enacted without widening the existing rules pertaining to unincorporated nonprofit associations.

The Model DUNAA establishes minimal default statutes that set forth the rules on particular matters absent contrary agreement with respect to the topic. However, given the nature of organizations that would adopt the entity, it is expected that a DUNA’s governing principles will govern most aspects of its operation. Generally equivalent to a partnership’s partnership agreement or an LLC’s operating agreement, the governing principles are the agreements of the members as to the purpose and operations of the association. The governing principles may be written or arise from conduct, with consensus formation mechanisms and on-chain governance proposals being specifically enumerated as acceptable forms of member agreement. The association, members and administrators are bound by the “governing principles” of a DUNA.

The critical features of the Model DUNAA are set forth below.

Formation, Purpose & Powers

A DUNA is an opt-in structure that can be utilized through election of the qualifying organization with the intent to form a DUNA and have at least 100 members. A DUNA is considered to be an entity distinct from its members and administrators and enjoys perpetual duration while being vested with all powers necessary or convenient to carrying out its purpose.

While for-profit activities are permitted, the proceeds thereof must be applied to the nonprofit purpose.

Liability for Association Debts & Obligations; Limited Liability; Suits By or Against a DUNA

Upon formation, members and administrators are afforded limited liability for its debts and obligations. A member or administrator is personally liable for his or own tortious conduct under all circumstances and is personally liable for contract liabilities on behalf of a DUNA if the member or administrator guarantees or otherwise assumes personal liability for the contract or fails to disclose that he or she is acting as an agent for a DUNA. A member or administrator is not otherwise personally liable for the tort or contract liabilities imposed upon a DUNA. A creditor with a judgment against the DUNA must seek to satisfy the judgment out of the DUNA’s assets but cannot levy execution against the assets of a member or administrator.

The one exception to the foregoing is the alter ego doctrine (also known as the veil piercing doctrine), which have been applied to unincorporated entities with liability protection. If the alter ego doctrine is found to be applicable, the separate entity status of a DUNA would be disregarded and the assets of the DUNA and its members and administrators would be aggregated and subject to a DUNA creditor’s claims in the same manner that a judgment creditor of a general partnership collects a judgment against the assets of a general partner in a partnership.

A DUNA may sue or be sued in its own name. Suit against a DUNA may be initiated on its registered agent or as otherwise provided by the law.

Members

Every DUNA must have one-hundred or more members. The one-hundred-person requirement for forming a DUNA is significantly more than the two-person requirement for the UNA and unincorporated nonprofit associations generally.

While the Model DUNAA is designed as technologically agnostic and does not require a DAO or utilization of distributed ledger technology, the existing use cases for a DUNA almost certainly requires some form of technology to meet the definition of “decentralization” as defined in the Model DUNAA. While decentralization cannot be established through an arbitrary number, the one-hundred-person requirement clearly surpasses any reasonable threshold where an organization, absent a managerial position, could function without a technological layer facilitating decentralized decision-making.

Although placing a one-hundred-person requirement does introduce the risk of inadvertent dissolution, the organizations best suited to utilize the Model DUNAA have memberships that are orders of magnitude larger than those at risk for inadvertent dissolution.

Decentralization

The DUNA is intended to be utilized by decentralized organizations, which are organizations that are not controlled by a person or an affiliated group of persons, organizations whose success or failure does not depend solely on the managerial efforts of any person or affiliated group of persons. As a result, the DUNA contemplates a baseline structure that does not include a management function, but instead allows for the selection of administrators with limited authorization to perform specific tasks authorized by the membership. This categorization aligns the Model DUNAA with applicable standards for decentralization under U.S. securities laws.

As a relative measure of centralization, many entity forms are capable of supporting decentralized operations. General Partnerships, member managed LLCs, LLPS, LCAs are all significantly less centralized than Corporations, traditional Cooperatives and manager managed LLCs, which themselves are significantly less centralized than a sole proprietorship. As such, decentralization itself is not a particularly relevant legal concept as the business formation laws are focused on who within the organization has responsibility of performing management function.

Administrators

The utilization of “administrator” throughout the Model DUNAA is an intentional distinction from the position of manager in an UNA or LLC where, as a general matter and absent countervailing facts, courts may see the position of manager as clothing its occupants with the apparent authority to take actions that reasonably appear within the ordinary course of operations. By requiring DUNA’s to specifically authorize the scope of authority, rights, and duties for each administrator, much of the confusion regarding management authority that currently exists across other entity forms will be remedied.

The actual authority of a DUNA’s administrator or administrators is a question of agency law and depends fundamentally on the governing principles and any separate contract between the DUNA and its administrator or administrators. These agreements are the primary source of the manifestations of the DUNA (as principal) from which an administrator (as agent) will form the reasonable beliefs that delineate the scope of the administrator’s actual authority.

Additionally, this limited authorization of authority for specific purposes fulfills the intent of the Model DUNAA to provide an entity form for decentralized organizations that exists without the need for the contractual limitations surrounding fiduciary duties common to entity structures that default to managerial authority and the fiduciary duties that come with it. However, it should be noted that eliminating an assumption of managerial responsibility from the Model DUNAA places a significant burden on DUNAs to narrowly empower the authority of administrators and to consider the obligations and duties arising from the application of agency laws to any authorization of authority. Further, DAOs seeking to pursue activities that necessitate managerial efforts should seek to use alternative legal entities designed to have managers.

Inspection of Books and Records

Members and administrators have the right to inspect association books and records. It should be noted that there is no requirement that any particular records be maintained by the association (including, no requirement that member listings be maintained), so the right of inspection only applies to what records have been maintained and if those records are maintained on distributed ledger technology to which the members and administrators have access – no further obligation to provide records exists.

Former members and administrators retain the right to have access to information to which they were entitled in those roles subject to some restrictions on access and use.

Property; Statement of Authority

A DUNA may hold in its name real, personal and intangible property. With respect to real property, the DUNA may file a “statement of authority” which creates a public record of the capacity for a person to, on the DUNA’s behalf, affect a transfer of the real property. There is no requirement of a statute of authority to transfer real property held in the name of the DUNA, but it presents an option to provide clarity of the capacity of the person signing on behalf of the DUNA.

Finance

A DUNA may not pay dividends or make other distributions to its members except for distributions that are allowed upon dissolution. However, a DUNA may pay reasonable compensation (including in exchange for participation in governance of the DUNA), reimburse expenses, confer benefits on its members consistent with its nonprofit purposes, or repurchase membership interests if doing so is authorized by the governing principles. 27

A DUNA has the capacity, but not the obligation, to indemnify its members and administrators from debts, obligation or liabilities incurred on behalf of the association. Administrators must have complied with any existing fiduciary obligations, if any, resulting from their role as administrator to be indemnified. If in a record, a DUNA’s governing principles may broaden or limit this right of indemnification.

Dissolution

A DUNA may be dissolved upon the satisfaction of certain conditions set forth in the law. It is important to note that dissolution and windup of a DUNA will require a greater degree of centralization than the decentralized operations detailed above to ensure that debts and obligations of the organization are satisfied. Accordingly, the provisions on dissolution and wind-up contemplate the need for decision- makers authorized with wide authority to effectuate the dissolution process.

Mergers and Conversions

The DUNAA provides for mergers and conversion between DUNAs and other organizational forms, assuming the law governing the other organization authorizes a merger or conversion with a DUNA and establishes the requirements for merger and conversion consistent with similar provisions of other business entities.

Relationship to Other Law

Principles of law and equity supplement the DUNAA. As the DUNA is its own freestanding body of law, it is not directed or otherwise indicated that the law of partnerships, corporations (whether for-profit or nonprofit), LLCs (whether for-profit or nonprofit) or any other body of organizational law shall serve as the “gap filler” when either the agreement for a particular organization or the DUNAA is silent. Rather, when the statute and the “governing principles” of a particular association are silent, the general principles of law and equity for the adopting state would control.

Tax Treatment

Questions involving federal and state income tax of a DUNA are not substantively discussed herein, as they are not a matter of state entity law.

However, it is important to note that if a DUNA were not already classified as a corporation for federal tax purposes at formation, it would be able to elect treatment corporate tax treatment by filing a Form 8832, Entity Classification Election. It is expected that every DUNA would operate as a corporation for federal tax purposes because it is operationally consistent and provides a better path to meet compliance obligations regarding the payment of any tax owed than pass-through taxation.

Additionally, one often misunderstood aspect of nonprofit organizations generally is that they are automatically treated as, or seeking to be treated as, tax exempt entities under IRC Section 501(c). Although some nonprofit entity forms are required to attain tax exempt status under 501(c) as a requirement to existence and 501(c)3 organizations are often granted particular benefits in areas like liability protections of volunteers - in general, tax exemption is simply a classification that qualifying organizations can attain, but it is not a requirement.

Model DUNAA Proposal

Linked is an annotated draft of the Model DUNAA, which contains commentary on the reasoning behind the construction of the various provisions. This proposal has been prepared in collaboration with industry experts from a range of organizations and is intended to be a starting point from which further input can be sought and obtained prior to formal law proposals being made to state legislatures across the United States.

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

Miles Jennings is General Counsel of a16z crypto, where he advises the firm and its portfolio companies on decentralization, DAOs, governance, NFTs, and state and federal securities laws. Previously, he was a partner at Latham & Watkins where he cochaired its global blockchain and cryptocurrency task force. He was previously a partner at Latham & Watkins. David Kerr is the Principal of Cowrie, where he uses 10 years of experience in tax strategy, financial accounting, and risk advisory in the industries of gaming, telecommunications, and technology-driven online sales platforms to assist clients with risk mitigation strategies on developing web3 issues.

↩ -

An abundance of use cases already exists for the tokenization of assets, streamlining of processes and expansion of automation through utilization of blockchain technology, see generally Blockchain Solutions – IBM Blockchain, available at https://www.ibm.com/blockchain?utm_content=SRCWW&p1=Search&p4=43700068512464068&p5= p&gclid=3b75ec747eda139f8c628f383de9df46&gclsrc=3p.ds; Blockchain – Deloitte US Perspectives, Insights, and Analysis, available at https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/consulting/topics/blockchain.html; and Blockchain solutions; and EY US Platforms, insights & services, available at https://www.ey.com/en_us/blockchain-platforms. ↩

-

Electric Capital Developer Report 2023, available at https://www.developerreport.com/developer-report- geography. ↩

-

See S.4356 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Lummis-Gillibrand Responsible Financial Innovation Act, available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/4356 and Updated 2023 Fact Sheet, available at https://www.lummis.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/Whats-New-in-Lummis-Gillibrand-2023-Final.pdf; H.R.4766 - 118th Congress (2023-2024): Clarity for Payment Stablecoins Act of 2023, available at https://www.congress.gov/ bill/118th-congress/house-bill/4766; S.4760 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Digital Commodities Consumer Protection Act of 2022, available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/4760; and FACT SHEET: President Biden to Sign Executive Order on Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets - The White House, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/03/09/executive-order -on-ensuring-responsible-development-of-digital-assets/. ↩

-

David Kerr and Miles Jennings, A Legal Framework for Decentralized Autonomous Organizations, a16z (October 2021), available at https://a16zcryptocms.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/dao-legal-framework- part-1.pdf. ↩

-

Miles Jennings and David Kerr, A Legal Framework for Decentralized Autonomous Organizations - Part II - Entity Selection Framework, a16z (June 2022), available at https://a16zcryptocms.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/ 2022/06/dao-legal-framework-part-2.pdf. ↩

-

For a list of proposed and enacted blockchain laws by state see the National Conference of State Legislatures, Cryptocurrency 2023 Legislation Summary, available at https://www.ncsl.org/financial-services/cryptocurrency- 2023-legislation. ↩

-

Although created to provide a legal entity structure for current applications of decentralized technology, the Model DUNAA’s use is not exclusive to DAOs or a particular utilization of technology. Any organization meeting the requirements would be eligible to form as a decentralized unincorporated association under the act. ↩

-

CA AB1229 - 2023-2024, Regular Session, LegiScan, available at https://legiscan.com/CA/bill/AB1229/2023. ↩

-

CA Legislature, Unincorporated Associations–Study B-501, available at http://www.clrc.ca.gov/B501.html. ↩

-

TX HB3768, 2023-2024, 88th Legislature, LegiScan. available at https://legiscan.com/TX/votes/HB3768/2023. ↩

-

Acts 2003, 78th Leg., Chapter 182, TX, available at: https://www.lrl.texas.gov/scanned/sessionLaws/78-0/HB_115 6_CH_182.pdf. ↩

-

Wyoming Legislature, SF0050 – Unincorporated nonprofit DAO's, available at https://wyoleg.gov/Legislation/20 24/SF0050. ↩

-

Senate File 066, 52nd WY Legislature, available at https://wyomingdigitalcollections.ptfs.com/aw- server/rest/product/purl/WSL/i/3e0deeac-a0d6-402f-b866-3293077fe514. ↩

-

This proposal is focused on the specific legal challenges and uncertainty facing DAOs that govern the operation and ownership of blockchain networks and smart contract protocols. Many industry participants are exploring the application of DAO models to other traditional operational models, including investment clubs, social clubs and collectives. Where a DAO pursues a traditional operational model that has a real-world analog, it will often be the case that the legal entity form suitable for the traditional operations is also suitable for such DAO. However, there are many cases where this premise fails, especially due to frictions in existing entity laws with centralized management and real-world operations paired with the relative anonymity and trustless nature of DAOs. Those issues would not be resolved by the adoption of the DUNA as those organizations would require significant member involvement in a managerial capacity, which is a question of function, not form. ↩

-

Credibly neutral systems are those that do not discriminate against any individual stakeholder or any group of stakeholders. This is thought to be critical in web3 in order to incentivize developers to build within ecosystems. See Vitalik Buterin, Credible Neutrality as A Guiding Principle, available at https://messari.io/report/credible-neutrality- as-a-guiding-principle. ↩

-

Stakeholder capitalism in web3 refers to the goal of designing systems that serve the interests of all stakeholders, rather than a certain subset of stakeholders. For example, in the traditional corporate world, equity holders are prioritized over all other stakeholders, including customers and employees. ↩

-

See Miles Jennings, Principles and Models of Web3 Decentralization, a16z (April 2022), https://a16z.com/wp- content/uploads/2022/04/principles-and-models-of-decentralization_miles-jennings a16zcrypto.pdf. See also Bruno Lulinski, David Kerr, The Center Will Not Hold: How Decentralization is Reshaping Technology and Governance, The Defiant (July 2022), https://thedefiant.io/decentralization-upends-governance/. ↩

-

Section 18025(a) California Corporations Code. ↩

-

Discussion of trusts, joint tenancy / tenancy in common, or any number of exceptions were excluded for clarity. Rather than lose the forest for the trees including all the history and rich complications – this section is written to simply explain some of the history of unincorporated associations and the evolution in vocabulary around them. It is exceedingly common for references to unincorporated associations simply to state the common law theory of liability or immediately turn to a discussion of charitable purpose. Like the frequent public references to “incorporating as an LLC” and “Limited Liability Corporations,” beyond simply being incorrect – this casual disregard for the role of states in entity formation creates an environment ripe for misunderstanding and potentially costly mistakes. ↩

-

See generally Richard A. Mann, & Barry S. Roberts, Unincorporated Business Associations: An Overview of Their Advantages and Disadvantages, 14 Tulsa L. J. 1 (2013), available at https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol14/iss1/1. ↩

-

Setting aside any complexity related to conflicting provisions, gap filling for missing provisions or treatment across courts of various jurisdiction - the above is simply stating that if a jurisdiction has statutes that reference specific rules for unincorporated associations and an LLC law with specific rules for LLCs – most likely, those statutes were constructed in a way that it is the LLC laws that would apply and not the provisions related to unincorporated associations generally. ↩

-

The 2008 act was referred to as the Revised Uniform Unincorporated Nonprofit Association Act (“RUUNAA”) until 2011, when the amended act reverted to the UUNAA (2008) (Last Amended 2011). However, as there are still nine jurisdictions who have adopted the original UUNAA – for clarity and as a reflection that both UUNAA and RUNAA jurisdictions presently exist, this paper continues to distinguish between the UUNAA and RUUNAA. ↩

-

Of the three states that have currently adopted blockchain or decentralized organization laws, only Wyoming has adopted the UUNAA. ↩

-

Although a DUNA could ostensibly recreate a traditional management structure through enacting governance proposals that reintroduced the concept of management, it would have to construct its governance proposals to a granular level of detail that would basically replicate existing entity forms that are intended to function in this way and there would be no situation where such an entity would not be better served as an UNA or other more appropriate entity form. ↩

-

The Model DUNAA also considered various state Unincorporated Associations, Vermont’s Blockchain Legislation, Wyoming’s DAO law and Tennessee’s Decentralized Organization (“DO”) law. ↩

-

Reasonable compensation is a somewhat amorphous concept as the standard of review is often defined by the activity itself and the purpose of the evaluative process. However, the general application provides a fairly intuitive measure in which compensation and its appropriateness can be evaluated in regard to payments and their underlying purpose. ↩