A Legal Framework for DAOs (Part II)

This post originally appeared on a16crypto.com in June 2022 as part of Miles Jennings and David Kerr's series on domestic legal entity frameworks.1

If you'd prefer to read this article in PDF format, click here.

DISCLAIMER: This analysis should not be construed as legal, business, tax or investment advice for any particular facts or circumstances and is not meant to replace competent counsel. None of the opinions or positions provided hereby are intended to be treated as legal advice or to create an attorney-client relationship. This analysis might not reflect all current updates to applicable laws or interpretive guidance and the authors disclaim any obligation to update this paper. It is strongly advised for you to contact a reputable attorney in your jurisdiction for any questions or concerns. The invitation to contact is not a solicitation for legal work under the laws of any jurisdiction. Please see http://a16z.com/disclosures for more information.

Introduction:

As more organizations form as Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (“DAOs”), the term itself is expanding to encompass a broad range of activities. The diversity of this activity is not only a reflection of the utility provided by blockchain and smart contract technology in building robust systems of decentralization and autonomous operations, but also the preexisting desire of numerous communities and organizations to implement an effective form of decentralized organization not bound by conventional limits on trust, geographical restriction or physical limitation.

The diversity of DAO activity combined with the lack of guidance in applying existing laws to digital assets continues to make entity selection a particularly difficult issue for DAOs to navigate. The broad use of the term DAO compounds this difficulty as anything beyond the most general discussions of DAOs necessitates differentiating specific characteristics and activities to be beneficial. As many DAOs have developed into organizational forms that would benefit from legal existence, identifying appropriate structures is particularly important because it is through those entities that DAOs interact with the real- world regarding contracts, liability and regulatory compliance.

Part I of A Legal Framework for Decentralized Autonomous Organizations sought to analyze a number of the challenges facing DAOs by providing a background on the U.S. regulatory regimes and U.S. tax reporting and payment requirements applicable to DAOs, reviewing existing structures utilized by certain types of DAOs, and introducing the Unincorporated Nonprofit Association (“UNA”) legal structure.

This Part II proposes a framework to assist DAOs in evaluating their own facts and circumstances to determine whether a legal entity structure is necessary and, if so, assist in identifying which of the available entity structures provides the most benefit. The foundation for this framework is a review and analysis of the key features of the available structures. While these features are mostly fixed, their importance and weighting have evolved and will continue to do so as this sector develops.

At present, web3 is expanding towards widespread adoption and reliable compliant entity structures in the face of regulatory uncertainty are essential to support that expansion. Accordingly, the level of pragmatism of a given feature warrants significant consideration and is prioritized throughout this framework when evaluating potential DAO legal entities.

As in Part I, the intended audience for this paper is DAO projects with significant U.S. membership and/or activity. This paper does not examine international issues faced by DAOs without a significant U.S. membership and/or activity. Overall, the comprehensive analysis contained herein strongly supports a conclusion that DAOs with significant U.S. membership and/or activity will be best served adopting U.S. domestic structures for reasons of decentralization, regulatory compliance, taxation and risk mitigation. This analysis is divided into two sections:

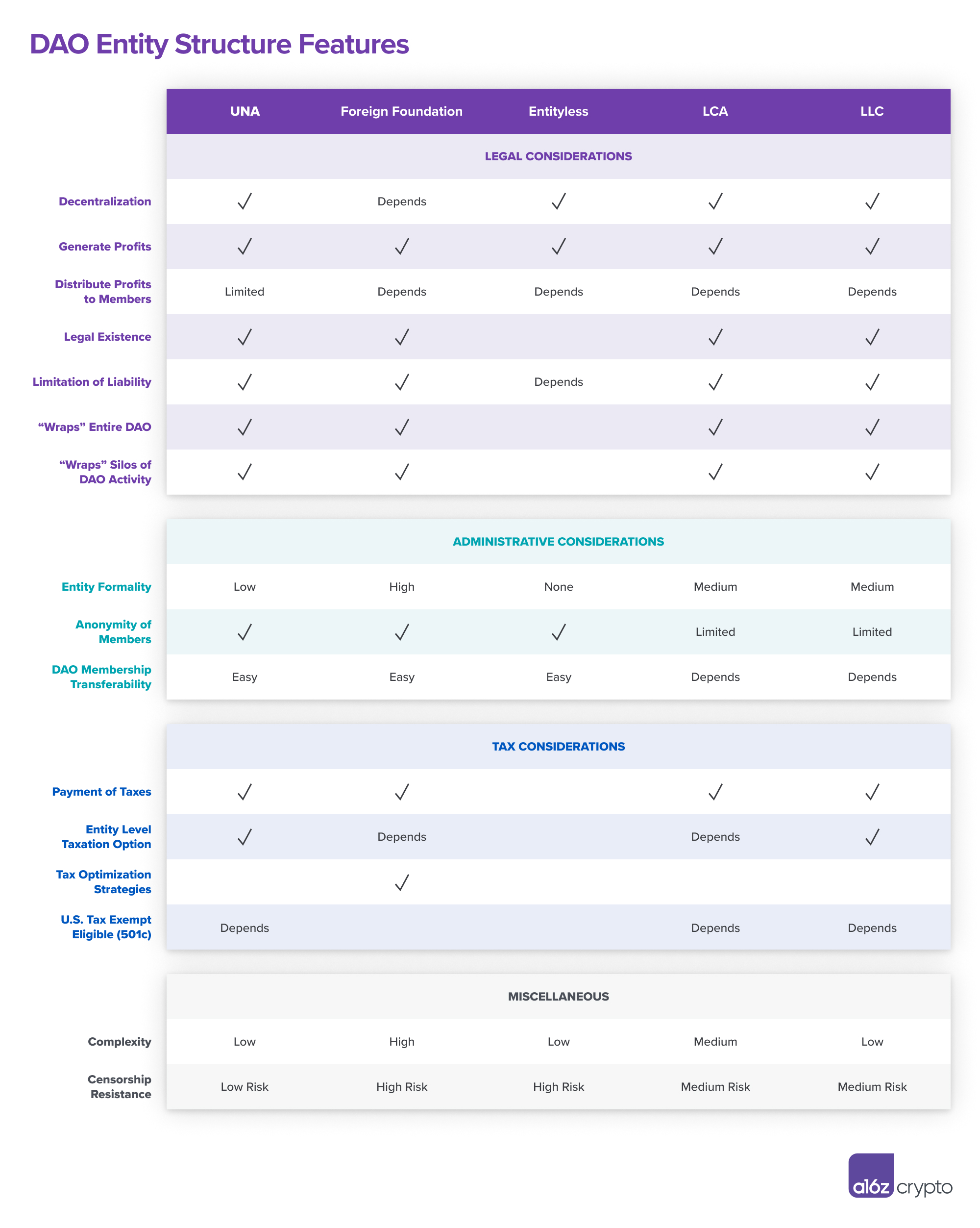

- Entity Structure Features – This section identifies and summarizes the relevant features of the entity structures most commonly used by DAOs. It is intended to provide builders and legal practitioners a useful comparison tool of the available structures.

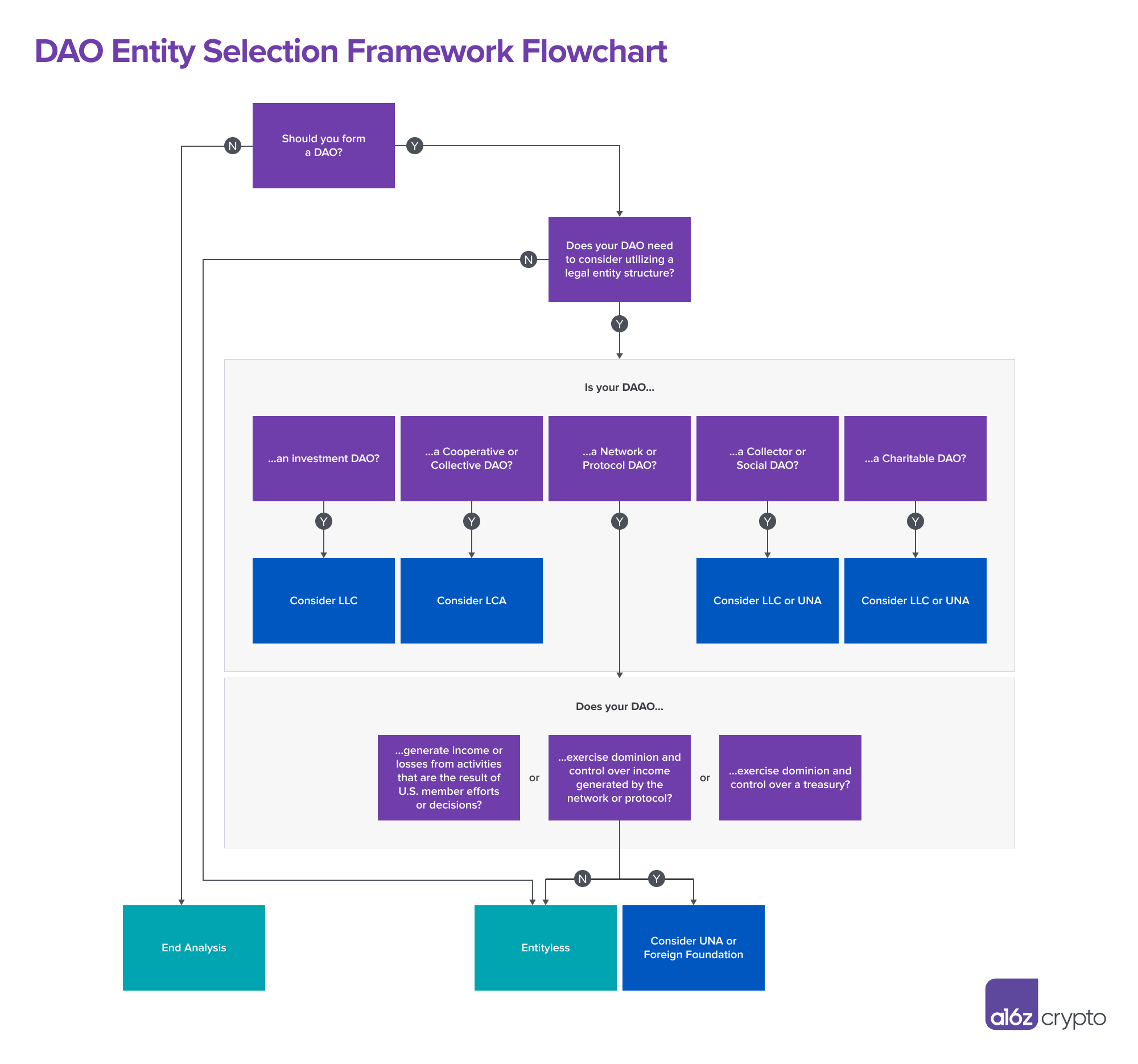

- Entity Selection Framework - This section provides a flowchart to guide builders and legal practitioners through the process of applying their facts and circumstances to the entity selection process. Additionally, Appendix A provides a brief summary of each legal entity structure discussed herein, including a discussion of primary advantages and disadvantages, a review of appropriate uses and a list of additional resources. Appendix B provides additional background on the tax concepts discussed herein.

* The facts and circumstances of significant U.S. membership limits the feasibility of foreign trust structures and foreign incorporated structures, as the reporting requirements and potential unfavorable tax treatment for U.S. members generally limits their usability. Although the Marshall Islands is often presented as a non-profit entity with tax benefits attributable to the United States – this is simply not an accurate representation of the entity’s treatment for U.S. taxation (absent such an entity being approved for tax-exempt status within the United States) and accordingly, this structure is discussed generally within this document as a Foreign Corporation.

** Discussed in more detail below, the Limited Cooperative Association (“LCA”) is a hybrid entity structure combining elements of a traditional cooperative and an LLC. Typically, this entity form is created through adoptions of the Uniform Limited Cooperative Association Act (“ULCAA”) and is most commonly utilized by DAOs registered in Colorado (“CULCA”).

*** LLCs are a common entity structure that has been utilized by DAOs in different ways (including by individual DAO members). Wyoming and Tennessee have both expanded their LLC legislation to include rules specifically designed for DAOs and Decentralized Organizations (“DOs”), respectively. Throughout this paper, comments made about LLCs are generally applicable to the WY and TN laws and distinctions are only drawn when pertinent.

Entity Structure Features

An understanding of a DAO’s operations and activities is necessary to ensure that the features and limitations of any entity structure support the intended purpose and needs of the DAO. The following discussion reviews various legal, administrative, tax and other considerations associated with the key features set forth in the table above.

Legal Considerations

Decentralization

A key consideration in determining the appropriate entity structure is balancing the required formalities with a DAO’s need to be decentralized. Many traditional legal entity structures require hierarchies (e.g., officers and boards of directors) and include concepts (e.g., stockholders, fiduciary duties, etc.) that are antithetical to notions of decentralization. Although the entity structures in the table above promote decentralization to different degrees, they all generally contribute positively to a DAO’s decentralization.

Of these structures, UNAs, LCAs and LLCs arguably provide the greatest foundation upon which decentralized operations can be built. This is primarily due to the significant operational and governance flexibility these structures provide.2 In addition, these structures do not require ongoing real-world human activity (i.e., actions by directors, officers or shareholders) for their continued operation, and such structures allow for fully on-chain governance and activity.

Entityless structures provide no restrictions on operational and governance flexibility, which forms a strong foundation for decentralization. However, because Entityless DAOs do not have a legal entity to act on their behalf, the developer corporations launching such DAOs sometimes experience difficulty moving activities that are exclusively DAO-activities (e.g., the management of the DAOs community and social media platforms) outside of the initial developer corporation. Such commingling of developer corporation activities and DAO activities could potentially be construed by authorities to undermine a DAO’s overall decentralization.3

Foreign Foundations also present unique challenges with respect to decentralization. In order for a Foreign Foundation structure to provide limited liability protection to a DAO, the structure necessitates off-chain actions to be taken by individuals (e.g., trustees, enforcers or foundation directors) at the direction of the DAO. DAO members are not actually members of the organization (nor are they owners). While limitations on the level of trust placed in the Foreign Foundation’s board can be included in its organizational documents, the relationship between DAO and Foreign Foundation can never be trustless. As a result, the reliance on such board could have implications for the decentralization of the DAO.

In addition, use of Foreign Foundation structures can present certain practical challenges relating to decentralization. For instance, depending on the expected scope of a DAO’s activities, decentralization could necessitate that the DAO’s Foreign Foundation be fully operational and independent of the original developer corporation. However, establishing a workforce to run those operations from within the Foreign Foundation’s jurisdiction can be difficult and if the workforce is domiciled outside of such jurisdiction (such as in the U.S.), such arrangement could be impacted by the tax considerations discussed in Appendix B. If a Foreign Foundation does not have any operations and instead, relies solely on the original developer corporation to take any action, the commingling of activities could potentially undermine the DAO’s decentralization.4 As a result, use of Foreign Foundation structure should be discussed with competent counsel prior to being implemented.

Generate Profits

Whether a DAO could generate profits is an important operational consideration for many DAOs. All of the legal entity structures in the table above permit such activity. A common misconception about the UNA is that it is unable to generate profits under applicable UNA statutes, however it being a “non-profit” is not a limitation on earning profits, but rather a requirement that it not pay dividends or make distributions to members except for those permitted by statute.5 As a result, whether a DAO generates profits is largely irrelevant for purposes of legal entity structure selection.

Distribute Profits

A related operational consideration important for many DAOs is the distribution of profits to members, which applied more generally represents a transfer of value between a DAO and its members. Such value transfer can happen in a variety of ways, some of which look similar to value distribution mechanisms of equities (e.g., proportional rights to DAO assets, redemption rights, dividends and buyback programs), while others look like payments in exchange for services (e.g., liquidity mining programs and staking).

Within the broad definition of DAOs, the transfer of value from the DAO to members can take a variety of forms. For investment DAOs and cooperatives, distributions of profits might be the entire purpose for which such DAOs were formed. For protocol and network DAOs, distributions of profits are viewed by many as a potential method to support native token prices. For collector, social and charitable DAOs, distributions of profits might not ever be desirable or permissible.

Regardless of the structure a DAO uses and how it intends to operate, providing DAO members with a right to the profits of the DAO or distributing profits to such members in a manner analogous to distribution mechanisms for equity may have significant implications under U.S. securities and tax laws.6

As a result, any such programs should be discussed with competent counsel prior to being implemented. To the extent a DAO and its counsel conclude that U.S. securities laws prevent distributions of profits to members or significantly increases the risk that DAO membership interests (most commonly denominated in tokens) may be deemed to be securities if profits are distributed, then any consideration of distribution of profits becomes largely irrelevant for purposes of legal entity structure selection.

If a DAO and its counsel determine that U.S. securities laws will not be an impediment to distributing profits to DAO members, then there are several entity structures available. For example, investment DAOs and certain collective DAOs often function as mechanisms to earn and distribute profits to their members and LLC and LCA entity structures meet those needs. Foreign Foundation structures also enable distributions, though such distributions may raise concerns under applicable U.S. tax laws, as discussed in Appendix B. As discussed above, UNA statutes are often more restrictive with respect to member distributions, with only a small minority allowing distributions of profit.

However, even if a DAO and its counsel make a determination that U.S. securities laws would not be an impediment to profit distributions, it would be a mistake to constitute network and protocol DAOs in a manner that replicates the world of equities and centralized businesses. While governance tokens often provide similar voting rights to shares of equity, the similarities between the two instruments often extend no further. Seeking to distribute profits to governance token holders via programs that are akin to corporate dividends or stock repurchase programs only makes the distinction of governance tokens from equity more opaque, which could weaken any argument that the regulatory frameworks applicable to such instruments should treat them differently.

Furthermore, profit distribution via dividends, buy-and-burn programs and repurchase programs should typically not be prioritized by network and protocol DAOs because they are an inefficient use of capital for most projects, especially in the early stages of a network or protocol DAO’s lifecycle. Such mechanisms incentivize idle and unproductive uses of the governance tokens by DAO members. Instead, DAOs should prioritize network and protocol designs and tokenomics that make their native governance tokens a productive component of their burgeoning decentralized economies. These mechanisms could include incentivizing governance votes, staking based curation, incentivizing desired contributions of capital or work, and underwriting protocol risks via safety modules, all of which could be rewarded with the same proceeds that were to otherwise be distributed via legacy programs. By incentivizing productivity, DAOs can make their decentralized economies more efficient and increase their economic output in ways unavailable to legacy companies obligated to prioritize short-term profits over long-term productivity.

Ultimately, programmable blockchain networks and composable smart contract protocols enable sophisticated decentralized systems to be built without intermediaries and without incentive structures that only optimize value for a limited number of owners. As a result, DAOs should adopt structures that accrue value to all participants in the autonomous free-market economies made possible by web3.

Legal Existence

As outlined in Part I, one of the primary benefits of utilizing a legal entity structure is to give the DAO legal existence that is separate and distinct from its individual members. As a separate entity, the DAO is conferred a variety of rights, which include the ability to contract, to hold real property, to pay taxes, to have employees and to sue (or be sued) in its own name. And the DAO being able to exercise these rights and function in this manner creates economic opportunity for the organization to expand its operations and reduces risk for its members, including developers, founders and investors.

Limitation of Liability

Whether a structure affords a DAO and its members with a limitation of liability is a critical consideration, particularly given the various legal issues and uncertainty facing DAOs. Although there are complexities to navigate to ensure the necessary formalities are observed for entities (e.g., avoiding reckless or dishonest conduct, keeping entity assets separate from personal assets, and maintaining sufficient separation between the entity and the activities of the founders and developers), most of the available entity structures have a proven history of providing limited liability or, at a minimum, clearly provides those protections within the text of the law.

Although the ability to create organizations independent of geographical consideration is one of the primary benefits of DAOs, the multi-jurisdictional nature of their activities does give rise to questions of conflicts of law: namely, whether an entity structure will be observed and respected outside of its jurisdiction of organization. In this context, the broadness of the activities undertaken by a DAO significantly complicates the process of definitively addressing the underlying risk this issue presents. Nevertheless, every DAO must consider its contacts with every jurisdiction with which it interacts to determine possible registration requirements of activities, locations of employees, potential liability and any resulting potential for conflicts of law.

This is a daunting exercise given the lack of geographical limitations on membership and diverse operations of most DAOs. However, like many of the decisions facing DAOs discussed herein, this challenge strongly suggests that most DAOs should prioritize adopting a legal entity structure as a means to contract around much of the liability risk associated with multi-jurisdictional activity. For example, DAOs with legal entity structures can enumerate exclusive jurisdiction and forum requirements in their organizational documents, terms of use/service, which DAOs can require members to agree to when claiming airdropped tokens, participating in decentralized governance or utilizing any websites operated by the DAO. Utilization of arbitration agreements could also reduce risks.

Many have rightfully pointed out that the UNA is a particularly untested structure in regards to limitations on liability. However, the limited case law is instructive regarding the effectiveness of limited liability for decision-making members and the UUNAA clearly enumerates that the UNA is a separate legal entity from its members. This clarification was the fundamental reason why the UUNAA was necessary because unincorporated associations did not convey this right under common law and as the laws in many jurisdictions have evolved to provide more protections, those expansions were not consistently applied.

Corporate Wrappers

As discussed in Part I, the question of whether to “wrap” an entire DAO with a legal entity structure or to just “wrap” certain siloed operations is dependent on a particular DAO’s operations and activities. If a DAO has limited activity, does not foresee substantial real-world activity or limits the ability to update its underlying network or protocol, it may only require a legal entity structure that “wraps” specific activities, such as grant programs or the DAO’s treasury.

DAOs that desire to “wrap” all activity in a single legal entity structure may choose from the available options set forth in the table above. In order for the protections of the legal entity structure to apply, a DAO’s activity must be undertaken by the legal entity itself. It is for this reason that a DAO utilizing a Foreign Foundation will often install a board that generally acts at the direction of the DAO, as opposed to the governance of such DAO being entirely on-chain. In the case of UNAs, LCAs and LLCs, governance token holders are actual members of the legal entity structure, thereby allowing for fully on-chain governance within the protections of the legal entity structures.

In addition to the foregoing entities, DAOs that only desire to “wrap” specific activity in a legal entity structure also have the option of utilizing foreign trusts in certain situations.7 Siloed structures would be most effective for wrapping a DAO’s treasury, including any grant program utilizing treasury funds. Use of siloed “wrappers” may also be used in conjunction with additional legal entity structures.

Administrative Considerations

Entity Formality

Entity formality assesses (i) the formalities that developer companies and DAOs must undertake to adopt a particular legal entity structure and continue its existence; and (ii) the operational flexibility such legal entity structures are afforded under the statutes providing for their creation and existence.

The legal formalities related to formation and continued existence of an entity typically encompass entity registration, other annual reporting requirements and tax payments. Ongoing compliance with such formalities is often required for the entity to maintain its good standing. Assessing the flexibility afforded legal entity structures under governing statutes is critical in determining their appropriateness for a given DAO’s operations and activities.

The statutes governing the DAO legal entity structures discussed herein range from being highly flexible (i.e., no membership formalities) to rigid (i.e., membership formalities, voting requirements, director requirements, etc.). Legal entity structures with minimal formalities and maximum flexibility are categorized as having “Low” entity formality, and legal entity structures with significant formalities and low flexibility are categorized as having “High” entity formality: • Entityless DAOs have no formalities and no limitations on operations. • UNAs were conceived as informal memberships, and their administrative complexity is minimal. Although there are optional filings to better effectuate the holding of property and the receipt of service, there are no filings required with the Secretary of State for an UNA and even the limited case law specifically contemplates the lack of formality of the members not being grounds for the entity to not be respected. • The ULCAA provides LCAs with significant flexibility, so long as its decisions on transferability, distributions and voting are aligned with the impact they might have on securities treatment, ability to make distributions, tax filings and informational requirements. • In general, LLCs allow for highly flexible operations. However, these entity forms present complications in maintaining member records and restricting anonymity, as discussed further below. In spite of being designed for decentralized organizations, Wyoming’s DAO law and Tennessee’s DO law are, in many ways, more restrictive than many of the available LLC options. • Foreign Foundations typically require registration in their jurisdiction of organization, and they can be very rigid in their operational requirements. To the degree Foreign Foundations and Entityless structures are able to demonstrate their treasuries are not ultimately under the dominion and control of U.S. DAO members, the utilization of foreign trusts provides an optimal method for distributing grants from the perspective of U.S. taxation requirements.

Failure to comply with the formalities required for any entity structure could result in a loss of the key benefits associated with such entity form. For instance, DAOs utilizing LCAs and LLCs are often required to attain and maintain member records to meet the required formalities of those entity structures. Although some jurisdictions do not require public disclosures of member records, in the event member records are required at the entity level, that requirement could severely limit the effectiveness of these structures as limited liability vehicles if that anonymity were relevant to a future cause of action or a DAO were unable to comply with a state or member inspection of its member records.8

Anonymity of Members

While many jurisdictions do not require that domestic entities publicly list their memberships, those jurisdictions still often require legal entities to attain certain information to comply with legal formalities and tax reporting. Given that anonymity is an essential characteristic of many DAOs, any DAO that wishes to maintain the anonymity of its members should prioritize such feature during the entity selection process. This is particularly critical for DAOs assessing the use of LLCs and LCAs because many of the relevant statutes for such structures may require member lists, which precludes member anonymity.

In addition to the impact of formality requirements on the ability of DAOs to maintain the anonymity of their members, DAOs must evaluate whether the Corporate Transparency Act (the “CTA”), part of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2020, will create a significant obstacle. Although the final rulemaking for implementation of the CTA has not yet been released, the CTA will require certain entities to report beneficial ownership information to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) if they are (i) created by filing formation documents with the secretary of state; or (ii) formed under the law of a foreign country and registered to do business in the United States.9

The “beneficial ownership” requirements under the CTA require reporting of all individuals that are beneficial owners of the entity upon its registration. On an ongoing basis the reporting requirement is limited to individuals who control more than 25% of the ownership interest and individuals who exercise “significant control.”10 Although most DAOs may not ever have members that cross the 25% ownership threshold or members that exert “significant control,” they must be able to demonstrate that a sufficiently robust process exists to evaluate those levels of control.

Given the severity of the penalties, entity forms like LLCs, LCAs and Foreign Foundations registered to do business in a U.S. state must anticipate what compliance with this law would mean for their operations.11 For DAOs that utilize flow-through taxation structures, compliance with the CTA would be relatively easy, as the information necessary for the CTA would already have been provided to file the tax returns. But for DAOs that wish to maintain member anonymity, compliance may not be possible as an LLC or LCA.

UNAs are expected to avoid the CTA requirements as they do not require filing with the Secretary of State and were explicitly excluded from Customer Due Diligence final rules of financial institutions, on which the CTA is largely based.

Finally, the anonymity afforded to DAOs by Foreign Foundation structures is also subject to geopolitical risks. For example, while the recent inclusion of the Cayman Islands on the EU Anti-Money Laundering blacklist and the Financial Action Task Force’s grey list is not necessarily representative of a change in policy around their treatment of informational reporting, it is a reflection of the current level of reporting compliance of entities formed in the Cayman Islands. It can be expected that the Cayman Islands will be under increased pressure to obtain additional information around all entities utilizing Cayman structures and to expand the scope of transactions selected for further examination.

Membership Transferability

Many DAOs utilize their native token as evidence of DAO-membership and as a mechanism to participate in the decision-making governance of such DAOs. Accordingly, for many DAOs, whether an entity structure permits DAO membership to be transferred merely through the transferring of the DAO’s native token or requires greater formality for membership transferability is an important consideration. The unrestricted transferability of membership is attainable through all the entity structures discussed herein, although many of the domestic U.S. options require electing to make memberships freely transferable in their organizational documents to attain this result. While unrestricted transferability is often desirable, DAOs must take into consideration whether such free transferability will interfere with their entity formality requirements or regulatory compliance (as discussed above).

Tax Considerations

U.S. tax considerations are particularly relevant when evaluating the merits of the available entity structures. Absent any meaningful guidance, planning in this space is constrained to utilizing established principles to quantify risk and develop reasonable tax positions within those limitations. For purposes of this paper, the tax considerations discussed in Part I as well as Appendix B have been distilled down into the following four features.

Payment of Taxes

Adoption of any of the legal entity structures set forth in the table affords DAOs with an ability to comply with applicable tax reporting and payment obligations, although the feasibility of meeting those obligations varies significantly depending on DAO activity. Entityless structures have no means of complying with applicable tax reporting or payment obligations, whereas the tax reporting and payment obligations of DAOs utilizing any of the domestic U.S. entity structures (UNA, LLC or LCA) are well defined.

Additionally, as discussed in Appendix B, the tax reporting and payment obligations of DAOs with significant U.S. membership that utilize a foreign structure, including the Foreign Foundation structure or Entityless structure, may be more complicated and less beneficial than they initially appear.

Entity Level Taxation Option

Entity level taxation is available for several of the legal entity structures included in the table above. For the domestic U.S. structures, both UNAs and LLCs enable DAOs to elect to be taxed as a corporation at the entity level.12 When faced with the administrative infeasibility of flow-through taxation (largely due to U.S. members of a flow-through organizations being responsible for annual income whether or not distributions were made, but also because of the anonymity of DAO members), entity level taxation is a tremendous feature.

Although a U.S. domestic entity electing corporate tax treatment would be subject to the federal rate of 21% on profits, it would remove the reporting complexity and payment obligations for individual members, as tax obligations and informational reporting could be restricted to payments, transfers above $10,000 and distributions (if there were any). Additionally, to the degree a tax treaty provides benefits to a U.S. entity, such benefits are much less of a burden to be taken at the entity level compared to being passed through to the members, which would require individual form filings and further differentiated rates of withholding.

As discussed in Appendix B, there is also uncertainty as to how U.S. tax laws will ultimately characterize Foreign Foundations. The U.S. government has significant authority and precedent for conforming foreign structures to its laws and if it were to determine that a particular DAO’s mechanization for providing direction to the Foreign Foundation directors was resulting in a distorted characterization of the DAO – recharacterization by the tax courts or the IRS could result in any number of situations with significant ramifications to the DAO. Accordingly, utilization of the Foreign Foundation structures cannot be mass produced and must be carefully considered based on the underlying facts and circumstances of each DAO.

Tax Optimization Strategies

Although no-tax jurisdictions provide significant benefit in offshoring of Internet-only activity away from the United States,13 the presence of U.S. members making contributions of value to income producing activities and exercising operational control even collectively, decreases the utility of such offshoring strategies. In the event a protocol was fully functional and not dependent on updates, maintenance, improvement or support, utilization of an offshore entity would present a path to tax optimization. However, absent the appropriate but limited facts and circumstances where this would apply to DAOs, utilization of such strategy could end up being less optimized than the rates of U.S. corporate income tax and leave the structure vulnerable to other taxing authorities.14

The benefits of foreign trust structures and foreign corporate structures with significant U.S. membership would largely be negated by laws intended to prevent the utilization of any such foreign structures for U.S. citizens to avoid their tax obligations. Foreign trusts are susceptible to being classified as foreign grantor trusts if U.S. citizens exercised dominion and control over the funding of the trust, which results in the potential for tax to be paid on the initial transfer, as well as leaving the grantors obligated for the ongoing tax responsibilities of the trust.15

501(c) Tax-Exempt Organizations

Federal tax law provides tax benefits to nonprofit organizations recognized as exempt from federal income tax under section 501(a) of the Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”). Charitable organizations as defined by IRC § 501(c)(3) are the most well-known tax-exempted organization, but tax exemption is available for a number of activities that may be applicable to DAOs, including IRC § 501(c)(4) – social welfare organizations, IRC § 501(c)(6) – business leagues and trade associations, and IRC § 501(c)(7) – social clubs.

What qualifies as a tax-exempt organization is a particularly subjective area of the law because of the manner in which the statutes and the case law developed, which was not as a uniform application of an objective construct. While all the tax-exempt organizations prohibit personal inurement of net earnings or assets of the organization to benefit any insider (i.e., a person who has a personal or private interest in the activities of the organization), the types of activities that constitute personal inurement depend on the purpose for which the organization is organized and ultimately was exempted from taxation.

However, any number of activities could place a tax-exempt organization’s status in jeopardy and tax- exempt organizations have numerous compliance requirements for recordkeeping, reporting and disclosures in order to maintain tax-exempt status and avoid penalties. A tax-exempt organization that does not restrict its participation in certain activities and refrain from others, risks failing the operational requirements for exemption from income tax and jeopardizing its tax-exempt status.

Although IRC § 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organizations are the most restrictive on activities because of their ability to confer tax deductions for charitable contributions, even the typical operations of a DAO treasury are problematic for any entity seeking tax-exempt status as the retention of percentage of governance tokens likely exceeds any allowable form of reasonable compensation and limiting the treasury to a charitable purpose would require significant off-chain controls established to operate in this manner.16

In spite of the additional disclosure requirements and limitations on activity necessary to demonstrate compliance with a tax-exempt purpose, many DAOs would be well suited to operate in areas that already qualify as tax-exempt under the law. Although meeting the requirements for tax-exemption would place limitations on a DAO’s ability to be anonymous and decentralized, exploration of tax-exempt purpose could be an area where DAOs excel, particularly in developing qualifying charitable organizations.

Miscellaneous Considerations

Complexity

The level of complexity associated with an entity structure should also be considered by DAOs. Structures with high complexity create a barrier for DAOs to implement them because they involve significant costs, greatly reduce the pool of legal and financial advisors available to assist with such processes, are less likely to be well-understood by DAO members and potentially introduce complications in the event such structures ever need to be dissolved.17 As a result, the simplest legal structures (i.e., UNAs and LLCs) should be prioritized. Popularizing simple structures could also help to democratize access to appropriate legal structuring for DAOs and legitimize their existence in the eyes of U.S. politicians and regulators.

Censorship Resistance

Many leading voices in the space have correctly noted that DAOs that avail themselves of legal entity structures that require government consent subject themselves to the risk of being censored by that same government.18 This belief was the foundation for the Entityless structures that permeated the industry in its formative years. However, that position has evolved in recent years to a balancing of concerns regarding censorship and the benefits provided by legal existence. Concerns over the U.S. regulatory environment, ambiguity in taxation and increased filings of lawsuits have consequently driven the vast majority of protocol and network DAOs to adopt Foreign Foundation structures.19 While the reasoning behind the utilization of Foreign Foundations is still valid and even appropriate depending on facts and circumstances of a given DAO, the environment in which they exist is rapidly changing and consideration needs to be given to the likely consequences of these structures becoming the dominant DAO form.

In the next wave of growth for the industry, the most successful networks and protocols will have too many users and too much income to be overlooked by regulators and would be attackers. Once this level has been reached, if it has not already, the desire to maximize censorship resistance through the use of Entityless or Foreign Foundation structures will likely be met with the most stifling censorship.20 With Entityless structures, that could come in the form of punitive taxes and numerous class actions brought against developer corporations and their founders. With Foreign Foundation structures, that could come through evolving interpretations and applications of U.S. tax laws by aggressive regulators acting on the uncertainty described in Appendix B. These restrictions will not be limited to U.S. regulators and could come from many different countries with many evolving perspectives on web3. The recent inclusion of the Cayman Islands on the EU Anti-Money Laundering blacklist and the Financial Action Task Force’s grey list are additional examples of censorship risk that can be quickly deployed.21

Compared to the growing international pressures on digital assets and the reality that DAOs with significant ties to the U.S. may not prove to be as far from U.S. regulatory authority as they hoped, utilization of U.S. structures, particularly the UNA, provides the potential for a more palatable regulatory environment from which to build. As discussed above, UNAs do not require consent to be formed and the formality associated with LCAs and LLCs is low compared to the Foreign Foundation structures.22 Furthermore, the flexibility to utilize corporate taxation allows significant retention of privacy for members, as concerns around tax avoidance justifying informational reporting can be mitigated by the payment of tax.23

Ultimately, it is not a coincidence that the structures and mechanisms pursued in an attempt to provide the greatest censorship resistance are the very structures and mechanisms that legitimize calls for regulation, ultimately resulting in the most censorship. In order to prevent stifling regulation, builders must collaborate pragmatically with regulators in developing compliance mechanisms that do not interfere with function.

Entity Selection Framework

Based on the foregoing features, a framework for DAO entity selection can be developed and broken down into three parts: (i) threshold matters; (ii) defining purpose; and (iii) network and protocol DAOs.

These questions are all reflected in the following flowchart, which only highlights characteristics where there is a significant distinction between how the key characteristics would impact a DAO’s choice in entity and cannot be relied upon as a thorough examination of all relevant factors. All decision-making regarding entity selection should be made with the advice of competent counsel.

Part 1: Threshold Matters

The entity selection framework begins with two threshold questions.

| Question 1: Should you form a DAO? |

|---|

| Explanation of Question 1: Within the broad definition of DAOs, many have been conceptualized to do things like own real property, cap carbon emissions, perform drone deliveries, provide banking or other financial services, run a business, partner with other existing businesses, launch satellites and any number of real-world purposes. Given the regulatory complexity and limitations of decentralization when viewed from the lens of traditional business operations, the decision to form a DAO should not be undertaken lightly. Simply layering minimal aspects of blockchain functionality and democratic voting onto an existing business operation for the purpose of tapping into the popularity of DAOs misses the benefits of building in web3 and creates significant regulatory, liability and taxation risks. As a result, if a project does not have a purpose associated with the blockchain, provide utility absent the need for centralized authority or a plan to develop the benefits of decentralization for its members, it requires a significantly different analysis of its requirements for legal entity structure and would not benefit from becoming a DAO. |

| Answer 1: If “Yes”, go to Question 2. If “No”, end analysis. |

| Question 2: Does your DAO need to consider utilizing a legal entity structure? |

|---|

| Explanation of Question 2: Assuming that a project should operate as a DAO, then the threshold question in determining which legal entity structure may be most appropriate for a specific DAO is whether a legal entity should be utilized at all. What appears to be a straightforward question quickly becomes complicated depending on the facts and circumstances of the DAO in question. For instance, many blockchain networks and smart contract protocols function free of human control and physical location, do not produce income and do not provide ownership rights to users. Rather, these technologies simply provide functionality and user connectivity analogous to protocols like HTML and SMTP, and accordingly, are simply the execution of computer code providing a foundation upon which operations and functionality can be built. In such cases, a legal entity structure should not be required. The historical distinction between human creators and the execution of computer code has led many leading voices within the space to develop philosophical opposition to the use of legal entity structures by DAOs. This perspective is founded on a belief that the adoption of a legal entity structure is counter to the idea that DAOs should exist solely in the virtual world, without borders and without being subject to government control or censorship. Implicit in this reasoning is a narrowly construed definition of a DAO where the autonomy of the process is the primary characteristic and decentralization is not representative of member voting, but rather the underlying trustless, permissionless and verifiable ecosystem provided by decentralized blockchains and smart contract protocols. However, the above description of DAOs as nothing more than consensus mechanisms built on top of software is not reflective of the evolving nature of many DAOs, which are often still developing and taking on new roles and forms. As outlined in Part I, the introduction of a treasury as a store of governance tokens controlled by the community, real-word interactions, production of income, ownership of assets, employment of persons and ownership of IP have resulted in organizational activities that may require entity structures to provide legal existence, limit liability and meet taxation obligations. Whether or not this broader activity rises to the level of being a DAO when defined narrowly is irrelevant to the reality that the utilization of blockchain technology providing member decision-making through the mechanizations of governance protocols has raised legal, operational and taxation questions that must be addressed under the current laws. Although there is no perfect legal entity structure available for most DAOs and the complexities of international tax and regulatory compliance are exceedingly high, DAOs must rise to this challenge in order to mitigate the risk to their members. |

| Answer 2: If “Yes”, go to Question 3. If “No”, consider Entityless. |

Part 2: Defining Purpose

For organizations that have established that they both wish to be a DAO and wish to evaluate entity structures, the next step is to determine the intended purpose of the DAO.

| Question 3: Is the DAO (a) an Investment DAO, (b) a Cooperative or Collective DAO, (c) a Network or Protocol DAO, (d) a Social or Collector DAO, (e) a Charity DAO? |

|---|

| Explanation of Question 3: The purpose of a DAO will often dictate which legal structure is most appropriate. A legal structure that is appropriate for one type of DAO (such as one formed for the purpose of overseeing a blockchain network or smart contract protocol) may not be suitable for a different type of DAO (such as one formed as an investment club). If a DAO’s primary purpose is to function in a manner for which real world analogs already exist (i.e., an investment clubs, cooperatives or charities), then the existing entity structures make an excellent starting point for determining DAO entity structuring decisions. |

| Answer 3(a): Investment DAO – LLC Investment DAOs are a particularly common type of DAO. These DAOs are typically formed as investment clubs, which are usually comprised of a group of people who pool their money to invest together, research possible investments as a group and make buy or sell decisions together, often as a result of a member vote. Investment clubs are generally eligible for an exemption from registration with the SEC, though such eligibility is dependent on an evaluation of a DAO’s facts and circumstances and the adoption of limitations on its activities (i.e., avoiding issuing membership interests that are securities, limitations of fewer than 100 members, not advertising openings within the club publicly and requiring every member to participate in voting). Investment clubs are typically formed as LLCs with flow-through taxation of its members. As a result, the entity selection decision is fairly straightforward for Investment DAOs that qualify as investment clubs. Investment DAOs that do not qualify as investment clubs will also likely wish to form as LLCs or utilize other structures typically used by investment funds. For more information on LLCs, see Appendix A. |

| Answer 3(b): Collective or Cooperative DAO – LCA To the degree a DAO is formed around a community that intends to pool resources and services with the intention of distributing profits based on membership contribution, DAOs should consider forming as Colorado Uniform Limited Cooperative Associations (“CULCA”). Intended as a hybrid structure, the entity form is highly flexible to the needs of DAOs. The entity’s pass-through taxation requirements are a limitation on anonymity (though if the entity elected to be taxed as a corporation, the application of the CTA would result in similar limitations) and even the most minimized corporate formalities inherent to this structure would not work for all DAOs. However, DAOs formed as cooperatives24, collectives25 and worker-based initiatives would likely benefit from the entity’s limited liability, legal personhood and token structuring, as well as additional benefits like health insurance and the potential for distributions based on patronage. For more information on LCAs, see Appendix A. |

| Answer 3(c): Network or Protocol DAOs → Go to Question 4. DAOs formed for the purposes of overseeing the operation and ongoing development of blockchain networks and/or smart contract protocols require a more in-depth analysis of their activities and operations in order to select the proper entity. For such analysis, proceed to Question 4 in Part 3 of this Entity Selection Framework. |

| Answer 3(d): Social or Collector DAOs – LLC or UNA Social DAOs are typically formed with the goal of establishing a community capable of trustlessly coordinating and sharing costs associated with group activities. Social DAOs may make use of an LLC structure or a UNA structure, with such selection likely being dictated by member anonymity and location of events. Foreign Foundations are most likely unsuitable for Social DAOs with significant real- world presence in the United States given the potential tax complications arising from such activity. For more information, see Appendix B. Collector DAOs often function similarly to investment DAOs, pooling resources and collecting art, often in the form of NFTs, and then facilitating the display of such art. LLCs are therefore also likely to be a good choice of legal entity for Collector DAOs. However, where a Collector DAO’s function does not necessitate the same limitations applicable to investment clubs, Collector DAOs may wish to expand beyond a number of members that is workable under the confines of flow-through taxation and elect corporate taxation as either an LLC or an UNA. For more information on LLCs and UNAs, see Appendix A. |

| Answer 3(e): Charitable DAOs – Nonprofit Corporations Charitable DAOs represent one of the strongest potential use cases for DAOs, however in many ways the path forward has yet to be truly explored because of the limitations on attaining tax-exempt status. The vast majority of Charitable DAOs are conceptualized with the idea that the members should receive value while doing good. Although this approach could ultimately prove highly effective as a concept, it is not indicative of what qualifies for tax-exempt status under the law. Any project considering a charitable DAO that is unwilling or unable to comply with those requirements must consider the likelihood that they will be considered a taxable entity. In the event a DAO is designed with the intention of attaining tax-exempt status, it is likely that significant disclosures would be necessary to demonstrate compliance with the requirements and compromises in decentralization would need to be made. Accordingly, utilization of nonprofit corporations would most likely be the appropriate entity structure. |

Additional Considerations Question 3 – Taxation:

Investment DAOs and Cooperative DAOs are atypical when compared to most DAOs in that they have a clean path to making distributions of profits to members, so long as their behavior conforms to the allowable rules (including applicable securities laws). Their creation is analogous to existing real-world organizations and is premised on making contributions to an organization and deriving the benefits of its success. As such, it is not surprising that their ability to meet the obligations of flow-through taxation presents fewer obstacles than for most DAOs.

Investment DAOs and Cooperative DAOs would have a relatively easy time calculating their inside basis (i.e., partnership’s basis in its assets) and outside basis (i.e., partner’s basis in its assets). Following the rules for contributions of property and allowing those contributions to be made tax free (which, if not a direct overriding of the IRS’ sub-regulatory guidance regarding the treatment of virtual currency, is certainly an application that extends the treatment of property beyond the level contemplated in that guidance) would allow DAOs in these situations to at least begin with the foundational accounting equation of Assets equal Liabilities plus Partners’ Capital Accounts.

Although some complexities would need to be assumed around the permissibility of deductions and, in the case of LCA’s, outside equity of investors - these projects could reasonably be considered viable candidates for flow-through taxation under the existing law.

Additional Considerations Question 3 – Real Property:

A significant number of DAOs (typically investment or social) have conceptualized owning or renting real estate as part of their operations. Although the United States does not place many restrictions on who may purchase U.S. real estate, the tax implications of foreign-owned U.S. real estate are considerable. Rental Income and the gains from selling or transferring U.S. property are sourced within the United States even when that property is not owned by a U.S. person or entity.

There is quite a bit of complexity in the reporting of foreign investors and foreign owners of real estate located in the United States, but at a high level the purposes of these requirements is to ensure that: (i) the foreign participants provide enough information to demonstrate that taxes should not be owed or that if owed they will be reported and paid appropriately; or (ii) potential tax is withheld from the transaction to such a degree the U.S. government has ensured full payment of taxes without having to perform additional collection.

DAOs that intend to interact with real property in the United States must identify the ways in which their operations would require additional compliance obligations, particularly regarding income tax.

Part 3: Network & Protocol DAOs

There are generally two available structures being utilized by network and protocol DAOs: Entityless and Foreign Foundation.26 Part I of this series and this paper propose the utilization of the UNA. While each of these structures offer a variety of features discussed in the previous section, the most relevant considerations in determining entity structure among legal, administrative and tax considerations often hinge on treatment under U.S. tax laws. As the application of U.S. tax laws to DAOs is facts and circumstances dependent, any entity selection for network and protocols DAOs should not be completed without the assistance of competent tax counsel.

However, the following three questions are designed to identify which network and protocol DAOs may not be able to truly benefit from an international entity structure because their U.S. activity would end up creating significant risk, cost and reporting obligations that might be better dealt with through the creation of a domestic U.S. structure. This same analysis is capable of being run for other types of DAOs (investment, collector, cooperatives, collectives, social, charitable), but this paper focuses on network and protocol DAOs, as they are the most complex and generally do not have real-world analogs.

| Question 4: Does the DAO generate income or losses from activities that are the result of U.S. member efforts or decisions? |

|---|

| Explanation of Question 4: The purpose of this question is to assess whether a network or protocol DAO’s activities may give rise to tax obligations of the DAO or its members. Given the unique structuring of DAOs, it is difficult to say what type of member activities might give rise to such tax obligations. On the one hand, if a U.S. developer corporation were directing the activities of the DAO, one might expect the IRS to attempt to look through the DAO directly to the developer corporation to determine that the income or losses of the DAO resulted from such developer corporation’s activities. Conversely, network and protocol DAOs that are decentralized could potentially be deemed to be less likely to generate income or losses from activities of their members. However, if a DAO generates ongoing income or losses from activities that are dependent on the efforts and participation of a DAO’s U.S. members and those activities occur in the United States, there is no foreign structure that will obviate the responsibility of the DAO to file a U.S. tax return and comply with reporting requirements. Utilization of a foreign structure in such a scenario could create punitive rates of taxation for U.S.- sourced income and any potential benefits of a tax treaty will not be available to jurisdictions that do not have tax treaties, or whose treaties are limited to informational disclosures (including Cayman Islands, BVI, Panama, etc.). Nevertheless, foreign structures (including Foreign Foundations), can be utilized regardless of member activity in the United States, but such use could create a number of potential filing requirements and tax obligations, with the penalties for non-compliance being severe. Projects that have the possibility of generating U.S. income or losses from the efforts of its members located in the U.S. should carefully evaluate whether the expected benefits of a foreign entity structure are truly superior to the options available in the United States. |

| Answer 4: Regardless of answer, go to Question 5. |

| Question 5: Does the Network or Protocol DAO exercise Dominion and Control over income generated by the Network or Protocol? |

|---|

| Explanation of Question 5: Most Layer 1 blockchain networks (e.g., Bitcoin, Ethereum, etc.) do not produce income. Although they typically have some form of governance mechanism, as well as developers, users and service providers (i.e., miners, validators, etc.), the service providers are usually the only parties to earn block rewards and fees paid by users, which are taxable to the service providers. Similarly, protocols that automatically route all fees directly to users do not produce income. For example, a decentralized exchange that automatically routes all trading fees to the providers of liquidity does not produce income, and such earned trading fees are taxable to the users when they receive them. However, where a DAO may exercise dominion and control over any income generated by a network or protocol, the DAO could potentially have tax reporting and payment obligations with respect to such revenue, which necessitates further analysis for purposes of selecting a proper entity structure. |

| Answer 5: Regardless of answer, go to Question 6. |

| Question 6: Does the Network or Protocol DAO exercise Dominion and Control over a Treasury? |

|---|

| Explanation of Question 6: IRS Notice 2014-21 and IRS Revenue Ruling 2019-16 have established that it is the IRS’ opinion that virtual currencies should be treated as property for U.S. federal income tax purposes. Accordingly, without a legal entity wrapping the DAO’s treasury activity or if such entity is deemed to be a flow- through structure for tax purposes, there is a risk that the U.S. members of a DAO are responsible for any realizable tax events associated with the governance tokens maintained within the treasury. While the functioning of Layer 1 blockchain networks, including their distribution of block rewards, can typically be altered through their governance mechanisms, such governance mechanisms typically do not have dominion or control over any existing store of the native digital asset of the network and thus, no treasury exists. In contrast, smart contract protocols deployed to blockchain networks often do have treasuries that are formed at the time of the launch of their native digital assets, and such treasuries are typically under the dominion and control of DAO members through governance protocols. Although the U.S. members should be aware they could ultimately have a tax obligation that includes penalties, a determination of each DAO’s facts and circumstances would be required to assess the best approach. The U.S. government has provided insufficient guidance to address the mechanics of how any tax obligations would be met and the existing law cannot be applied in a definitive way. It is unclear how the IRS could impute partnership interests without member ownership in the DAO and simply trying to utilize the contribution of property rules for partnerships quickly turns into an exercise in the absurd when every partner’s capital account is zero. |

| Answer 4, 5 & 6: As reflected in the flow chart, answers of “No” to Questions 4, 5 and 6 leads to a conclusion that an Entityless structure is a viable choice. This is reflective of what can be observed within web3, which is that most L1 blockchain networks do not have legal entity structures in place for their governance mechanisms. In such cases, legal entity structures are likely unnecessary given that L1 blockchain networks do not generate income from U.S. members, token holders do not have dominion or control over any network income and L1s typically do not have treasuries. For any smart contract protocols deployed to blockchain networks, the answers to Questions 4, 5 and 6 depend on the facts and circumstances of their DAO, and in some cases, may even change over time (i.e., if a protocol fee switch were turned on to enable the protocol to accrue fees). Although it is possible that the U.S. members of a DAO answering yes to Questions 4 and/or 5 would be in a situation where they were obligated to report income or make information filings on their individual tax returns, whether or not the DAO itself would have a filing requirement is significantly less certain. The lack of regulation and guidance on this issue presents a number of reasonable interpretations of various facts and circumstances – but they must be undertaken with great consideration and expertise. Unless a reasonable position can be formulated that the DAO for a smart contract protocol could not have any U.S. tax obligations (reflective of a “No” to each of Questions 4, 5 and 6), there is significant risk in foregoing the adoption of a legal entity structure that would enable the payment of taxes. That narrows our entity selection for a DAO that answers “Yes” to any of Questions 4, 5 and 6 as either an UNA or a Foreign Foundation. As discussed in Appendix B, the Foreign Foundation involves uncertainty from a U.S. tax law perspective and may not offer any benefits if the answer to Question 4, 5 or 6 is “Yes”. Meanwhile, wrapping the DAO in an UNA and electing for corporate taxation provides certainty and clarity with respect to the DAO’s tax position in regard to the U.S. and provides a starting point for assessing international and state obligations. If all of the features set forth in the table in the “Entity Structure Features” of this paper are assessed, the UNA is superior to the Foreign Foundation in a number of regards, including its support for decentralization, low entity formality, certain tax status, ability to qualify for tax-exemption, low complexity and pragmatic resistance to censorship. Conversely, the Foreign Foundation enables DAOs to distribute profits, to optimize their tax obligations and to avoid near term government censorship. However, as discussed in Appendix B, these benefits come with uncertainty, which exposes DAOs using the Foreign Foundation to potential censorship risks. |

Conclusion

Confusion about the use of legal entity structures for DAOs persists for a number of reasons, including the novelty and constantly expanding activity of DAOs, the lack of a well-trodden path for utilizing domestic U.S. entities for DAOs, the lack of detailed and constructive guidance from the IRS and SEC regarding the paradigm shift taking place in the use of DAOs and the general uncertainty of the U.S. regulatory environment. All of these reasons make the historical use of Entityless structures and the current prominence of Foreign Foundation structures both understandable and defensible.

Moreover, the impracticality and infeasibility of treating Entityless DAOs as general partnerships is readily apparent to anyone familiar with the workings of DAOs and the benefits of legal existence, limitation on liability and ability to contract afforded to DAOs utilizing Foreign Foundation structures are clear. However, the benefits of these structures come with significant detractors, and when viewed pragmatically, are easily surpassed by the benefits and certainty of the domestic U.S. structures discussed in this paper.

As demonstrated by the review of all the essential elements of applicable entity structures, the most pertinent distinctions all arrive through a comprehensive evaluation of taxation and how that fits into the larger regulatory environment. Although the existing entity structures have varying degrees of success navigating the needs of DAOs, the solutions in place are all viable when analysis is limited to exclusively administrative and legal concerns (although even then, the benefits of U.S. domestic structures do provide cleaner paths to decentralization and censorship resistance). However, when a comprehensive analysis is performed inclusive of U.S. tax concerns, the practical benefits of U.S. domestic structures for projects with significant U.S. membership and contacts is clear.

Given the recent failures in strategy and judgment within the web3 industry, DAOs should consider whether a passive approach of utilizing no-tax jurisdictions to wait for regulation to be applied to them is really the best course of action for web3. While web2 companies continue to be able to utilize no-tax jurisdictions to perpetually avoid payment of tax, there is growing criticism of such strategies and the international community is increasingly united against allowing this practice to continue. The replication of such tax strategies by the emerging web3 ecosystem could substantially increase the risk of global backlash, with the added risk of web3 offering up a less established and more attractive target for regulators.27

Further, it is worth questioning whether the adoption of such tax strategies is workable given the value proposition of web3. Offshoring in web2 continues to be an effective tax avoidance vehicle largely due to the web2 model where users have no value beyond the sale of their personal information and are simply a revenue stream for Internet activity housed outside the border of the United States. Although the networks and protocols of web3 could potentially benefit from these same strategies, their use could result in considerably different outcomes. This is due to the fact that such networks and protocols, and the projects built on top them, will depend on contribution of value from DAO members across the world, who will be compensated for their contributions. Those users will be in geographical locations that will impact the tax analysis of the underlying organization, and to the degree contributions from such members are being compensated, extremely complex tax situations will arise. Accordingly, web3 may have a difficult time adopting web2’s tax strategies as member value becomes more prominent.

DAOs utilizing corporate forms to pay entity level taxation can take the burden off members being responsible for the reporting and payment of taxes under existing tax rules. They can also present a cleaner path towards retaining member anonymity because many of the requirements around informational reporting are tied to ensuring tax is being paid. If tax is being paid, the justification for those requirements is significantly reduced.28 Critics of this approach will point to the cost and impact that will have on the ability to build, largely missing the point that the tax obligations exist regardless of whether they are being paid.29

Meeting the tax obligations to the jurisdictions in which they are owed (not just to the U.S.) is the single biggest opportunity to lay the foundation for meaningful building. A willingness to meet that obligation before being forced to comply would drastically change perceptions of the worth and sustainability of DAOs at all levels of government and could help secure the passing of legislation necessary for DAOs to continue to develop and grow with regulatory clarity.

An expansion of the unincorporated form (i.e., the UNA) as applied to DAOs is philosophically aligned with the informal construction of DAOs and the intent of the modern trend of affording unincorporated associations legal existence across many U.S. states. Demonstration of the value of web3 to state legislatures is essential in developing laws that can ensure DAOs act as good citizens in matters of taxation and overall value creation. Accordingly, the authors of this paper look forward to working with state legislators to accomplish these objectives and to encourage all of web3 to continue building.

Appendix A

Entity Summaries and References

| Unincorporated Nonprofit Associations |

|---|

| Overview The Unincorporated Nonprofit Association (“UNA”) entity structure is available in dozens of U.S. states, mostly as modified versions of the Uniform Unincorporated Nonprofit Association Act. UNAs offer DAOs a simple pathway to legal existence, enable a flexible operating structure and provide censorship resistance, all while promoting decentralization. |

| Best Suited For Network and protocol DAOs with significant U.S. ties, including subDAOs thereof. Also, non-investment and non-LCA DAOs with significant U.S. ties, including social DAOs and collector DAOs. |

| Primary Advantages The UNA solves three of the biggest challenges facing Entityless DAOs: (i) lack of legal existence (inability to contract or own property); (ii) inability to pay taxes; and (iii) potential unlimited liability. The full “wrapper” use case enables the vehicle to provide all DAO members with limited liability with respect to any DAO actions, but the structure can also be narrowly tailored to wrap specific DAO activities (e.g., treasury management). As compared to the Foreign Foundation structure, the UNA: (i) is better aligned with the principles of decentralization (the UNA’s limited liability protection can extend to purely on-chain governance actions and it does not require a board) and is a more practical option for achieving decentralization; (ii) provides certainty with respect to tax treatment by enabling taxation as a corporation (thereby avoiding much of the uncertainty described in Appendix B); (iii) does not require registration with the state in which it is formed and has low formality requirements; (iv) is significantly less complicated, time consuming and costly to organize; and (v) offers greater pragmatic resistance to government censorship that is more likely to be sustainable over the long-term. Additional benefits of the structure include that it permits membership to be denoted by token ownership, thereby enabling efficient transferability, and does not require members to disclose their identity. Finally, while the name includes “nonprofit”, the structure permits the generation of profits and compensation for member contributions. |

| Primary Disadvantages While UNAs as an entity form are eligible to attain tax exempt status depending on activity, the UNA structure is generally not tax optimized. In addition, depending on what state the UNA selects for organizing, there is a risk that such entity structure may not be recognized by other states, though much of this risk may be mitigated through contractual protections. Finally, there are limitations on the ability to distribute profits to members. As a result, for DAOs who are not otherwise prohibited from profit distributions under U.S. securities laws, the UNA could be overly restrictive. Additionally, member distributions of profits would invalidate the protections of the UNA if they were to exceed what was allowable under the law. |

| Additional Information - LFDAOs: Part I - https://medium.com/lexdaosim/legal-wrappers-and-the-lexdao-constitution-ba89e46a644c - https://stanford-jblp.pubpub.org/pub/rise-of-daos/release/1 |

| Foreign Foundation |

|---|

| Overview The Foreign Foundation entity structure is the most common structure currently in use by network and protocol DAOs (most commonly structured as a Cayman Islands HoldCo, with the inclusion of a B.V.I. OpCo (depending on activity and VASP reporting requirements)). These structures were first utilized as non-profit vehicles to oversee the future development of blockchain networks (e.g., the Ethereum Foundation), but are now more commonly used to provide an “ownerless” legal entity structure for DAOs in which the fiduciary obligation of the entity is to the purpose specified in the formation documents rather than to shareholders. |

| Best Suited For Network and protocol DAOs, including subDAOs thereof. Also, non-investment and non-LCA DAOs, including social DAOs and collector DAOs. |

| Primary Advantages The Foreign Foundation solves the three biggest challenges facing Entityless DAOs: (i) lack of legal existence (inability to contract or own property); (ii) inability to pay taxes; and (iii) potential unlimited liability. The full “wrapper” use case enables the vehicle to provide all DAO members with limited liability with respect to any DAO actions, but the structure can also be narrowly tailored to wrap specific DAO activities (e.g., treasury management). In addition, the structure can provide an extremely flexible framework and, to the extent DAOs are able to navigate complexities relating to (i) international ownership and control; and (ii) risks of foreign sourced income, the structure provides DAOs with optimized taxation strategies regarding payments and reporting requirements. Additional benefits of the structure include that it does not restrict DAO membership from being denoted by token ownership, thereby enabling efficient transferability, and does not require DAO members to disclose their identity. Finally, the structure permits the generation of profits and, subject to applicable securities laws, distribution of such profits. |

| Primary Disadvantages The Foreign Foundation is among the most complicated, time consuming and costly to implement, requiring an international transfer of intellectual property and compliance with strict independence requirements between the DevCorp and the foundation. The impact of such structure on the overall decentralization of a system is uncertain given that the board of the Foreign Foundation acts on behalf of the DAO, rather than the DAO directly acting for itself. While the need for trust can be minimized through various contractual arrangements, there are considerable practical limitations relating to the structure that can make decentralization more difficult to achieve. DAOs with significant U.S. ties (including U.S. membership) that use this structure must carefully consider the potential for the DAO members taking tax responsibility of the foundation’s activities, as discussed further in Appendix B. Finally, while the Foreign Foundation is perceived to offer significant government censorship resistance, it is far more susceptible than domestic U.S. structures to vectors of attack from regulators all around the world, especially when combined with a no-tax or blacklisted / greylisted reporting jurisdiction. |

| Additional Information- LFDAOs: Part I - https://www.careyolsen.com/briefings/overview-cayman-islands-foundation-companies - https://www.ogier.com/publications/the-foundation-company-as-a-decentralisedautonomous-organisation-dao-in-the-cayman-islands# |

| Entity Summaries and References: Entityless |

|---|

| Overview The Entityless structure is the default structure when any DevCorp or group of persons launches a token and decentralized governance (including via a multisig wallet). |

| Best Suited For Layer 1 blockchain networks without token-based governance and pure cryptocurrencies with no associated network or protocol. Also, network and protocol DAOs that do not produce revenue and have demonstrable technical decentralization, legal decentralization, and autonomy through the execution of immutable code. |

| Primary Advantages The Entityless structure has no formality, affords DAOs a high degree of decentralization and maximum autonomy, with no governmental interaction or ownership. Additional benefits of the structure include that it permits membership to be denoted by token ownership, thereby enabling efficient transferability, and does not require members to disclose their identity. Finally, the structure permits the generation of profits and, subject to applicable securities laws, distribution of such profits. |

| Primary Disadvantages The Entityless structure leaves DAOs unable to establish legal existence, unable to pay taxes and with a lack of clarity regarding limitations on liability. The lack of legal existence means that Entityless DAOs have no vehicle to (i) hold interest in IP, hold real property or contract without a member taking on individual responsibility; (ii) sue to enforce a right; or (iii) provide a structure conducive to expanding any real-world operational interactions. The inability to pay tax leaves members significantly exposed to any relevant jurisdiction asserting claims of taxation for its activities and the potential for unlimited liability, at the very least, exposes members to nuisance claims trying to assert liability. The foregoing limitations can hinder decentralization for network or protocol DAOs launched by DevCorps, as they can result in commingling of DevCorp and DAO activities post DAO-launch, which could be construed by authorities to undermine a DAO’s overall decentralization. Finally, while the Entityless structure is perceived to offer significant government censorship resistance, it is not a viable solution for the long-term development of web3 and is susceptible to vectors of attack from regulators all around the world. |

| Additional Information LFDAOs: Part I |

| Limited Cooperative Associations |

|---|

| Overview Cooperatives are an evolution of the traditional corporate form incorporated under separate statutes that convey unique legal features. Several DAOs have incorporated as cooperatives, particularly in the state of Colorado, which has adopted the Uniform Limited Cooperative Association which provides more flexibility in matters of corporate formality. |

| Best Suited For Cooperatives, collectives, and worker-based initiatives. |